Christians are the most persecuted of any religious group and face near-genocidal levels of oppression in some parts of the world, says a report commissioned by the UK Foreign Office.

Prepared by Reverend Philip Mounstephen, the Bishop of Truro and an Anglican missionary, the report estimated that one in three people worldwide experience some form of religious oppression, finding Christians are the most widely targeted group.

“Evidence shows not only the geographic spread of anti-Christian persecution, but also its increasing severity,” said the report, adding that “in some regions, the level and nature of persecution is arguably coming close to meeting the international definition of genocide.”

British Foreign Secretary Jeremy Hunt, who commissioned the study last year, said on Friday that “political correctness” played a role in the abuses, slamming governments around the world for being “asleep” on the issue.

“What we have forgotten in that atmosphere of political correctness is actually the Christians that are being persecuted are some of the poorest people on the planet,” said Hunt.

The report focuses on faith-based persecution in the Middle East, Africa, Asia, and Latin America – notably excluding Europe and North America.

“I think there is a misplaced worry that it is somehow colonialist to talk about a religion that was associated with colonial powers rather than the countries that we marched into as colonisers,” said Hunt, apparently wishing to forestall any discussion of Britain’s colonial presence in many of the regions mentioned in the report, and its role in stoking sectarian tensions. Britain administered much of the Middle East after the First World War, for example, as well as present-day India and Pakistan.

According to the Bishop of Truro, followers of Christ are at risk of being “wiped out” in the birthplace of Christianity. From 20 percent of the population in the Middle East and North Africa a century ago, that figure has fallen to just 4 percent today.

Unfortunately, the word “invasion” does not appear in the interim report even once – as in, the 2003 invasion of Iraq by the US-UK “coalition of the willing.” The invasion and occupation unleashed sectarian violence – including the rise of Islamic State (IS, formerly ISIS/ISIL) in Iraq and Syria. The report does note that the number of Iraqi Christians fell from 1.5 million “before 2003” to about 120,000 at the present, and in Syria from 1.7 million in 2011 to below 450,000 today.

With the UK and its NATO allies favoring “regime change” in Damascus, however, it is politically incorrect to point out that Syrian Christians are safe in territories controlled by the Syrian government, but persecuted in parts of the country under control of Western-backed “moderate” rebels such as the “Army of Islam” or “Front for Conquest.” Also on rt.com ‘Organ traders, terrorists & looters’: Evidence against Syrian White Helmets presented at UN

Yet the British Foreign and Commonwealth Office has been at the forefront of granting asylum in the UK to “White Helmets.” Those so-called civil defense units operate exclusively in areas controlled by Islamist militants, where Christians are most endangered.

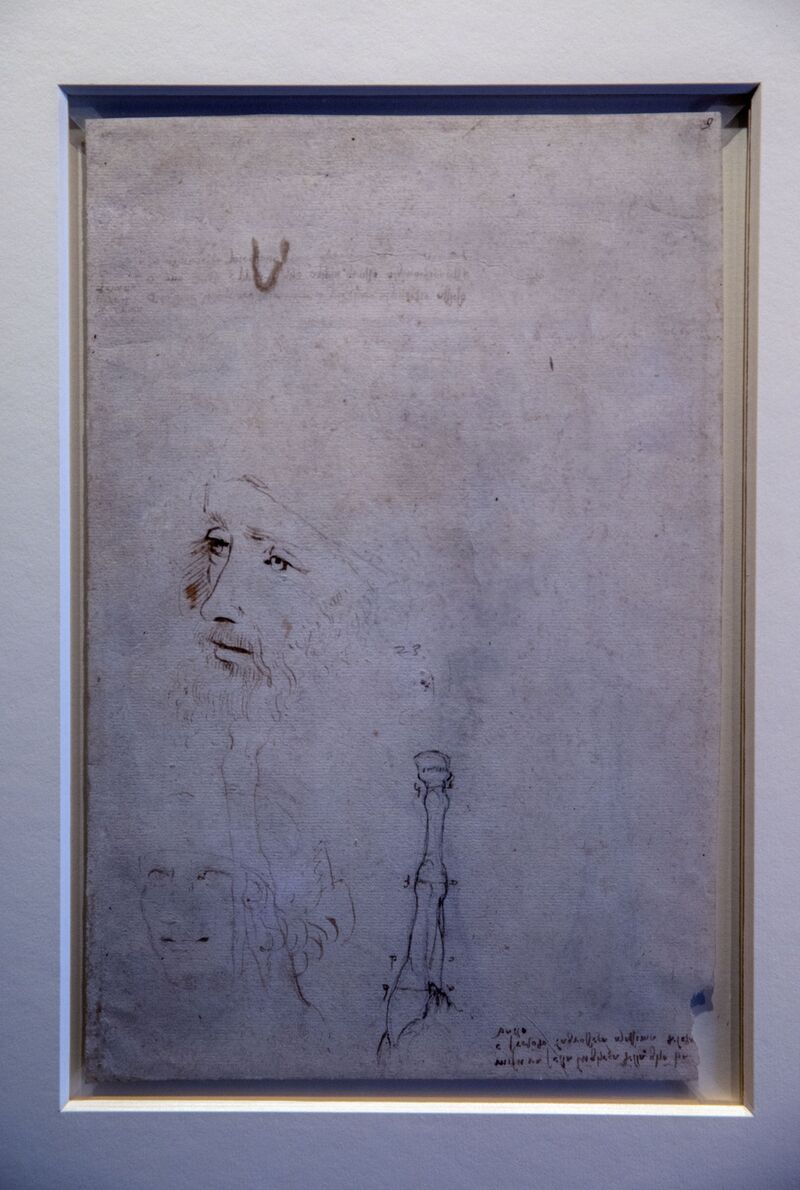

Introduction

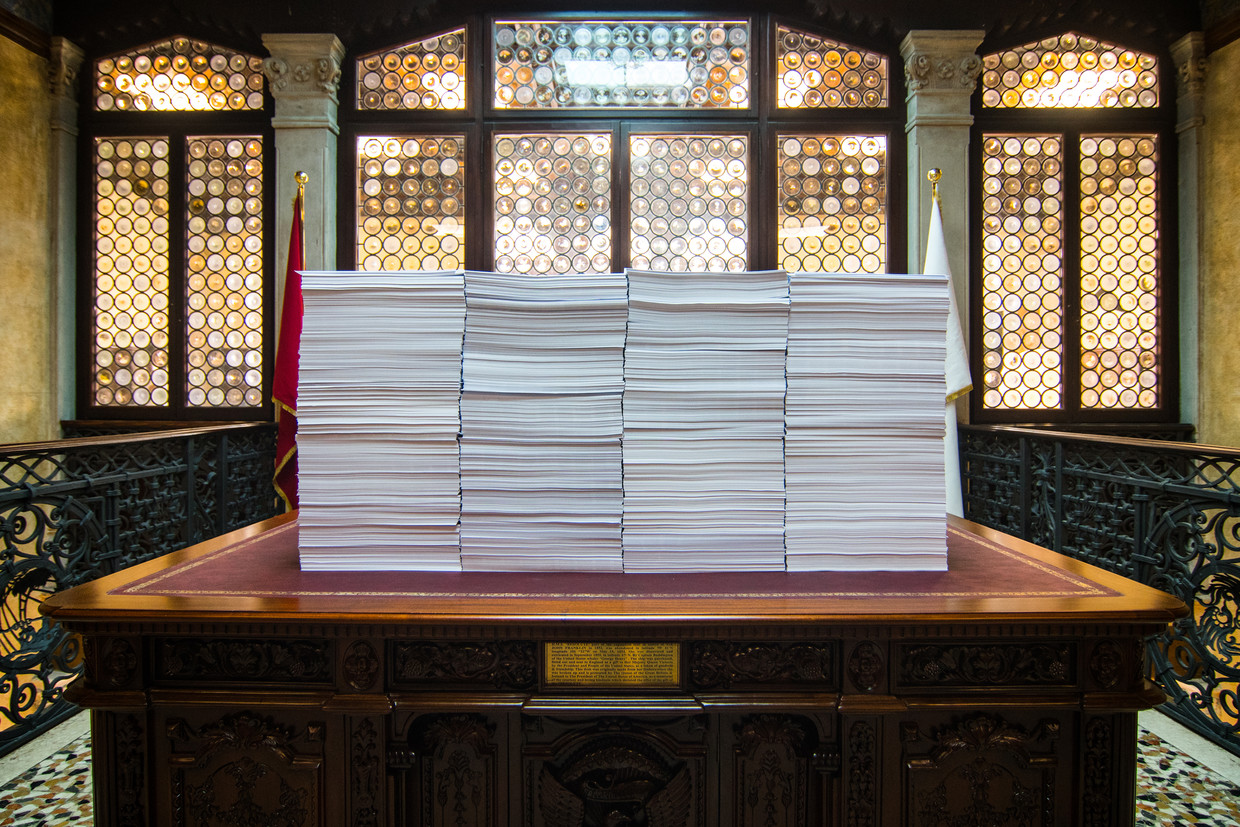

On Boxing Day 2018 The Rt Hon Jeremy Hunt MP, HM Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs, announced that he had asked me to set up an Independent Review into the global persecution of Christians; to map the extent and nature of the phenomenon; to assess the quality of the response of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO), and to make recommendations for changes in both policy and practice.

Initially, the aim was to conclude the Review by Easter 2019. However it rapidly became apparent that the scale and nature of the phenomenon simply required more time. Thus it was agreed that an Interim Report focusing on the scale and nature of the problem would be produced by the end of April 2019, with a final report to be delivered by the end of June. This present work is that Interim Report.

After an ‘Overview’ section, which paints a grim global picture, the Report then drills down into analysis of a number of different regions. Detailed analysis of the crisis Christians are facing in particular ‘Focus Countries’ will be added incrementally to the Independent Review’s Website over the next two months with case studies that will be used to review the FCO response. It concludes by drawing some general conclusions that will inform the second phase. It is on the basis of these conclusions and our engagement with all levels of the FCO that the Independent Review will then make its recommendations for policy and practice.

The independence and thus the credibility of the Review has always been of paramount importance to me. Therefore the make-up of the team working on this project has been a careful balance of FCO staff, secondees from key NGOs and independent members. I want to record my personal thanks to (amongst others) Tom Woodroffe, Julian Mansfield, Margaret Galy and Jaye Ho from the FCO. I am grateful too for expert input from Open Doors, Aid to the Church in Need, Release International and Christian Solidarity Worldwide. Finally, my grateful thanks go to independent members, David Fieldsend, Charles Hoare and Rachael Varney to whose hard work and dedication I am indebted.

Even while this Interim Report was in its final stages the news was coming in of the Easter bombings in Sri Lanka that reaped a horrific death toll in attacks in which Christians were a prime target. The sad fact is that this report will be out of date even by the time that it is published. And such is the sheer scale of the problem that whilst we have ranged widely in our analysis we make no claim to be wholly comprehensive. Originally we planned to focus on four regions however NGO colleagues then suggested two more. But the picture remains incomplete. In particular we have not analysed the situation in Europe and Eurasia. But our not doing so should not be taken to imply there is no issue to be addressed in this region. Far from it.

The Independent Review was announced at Christmas and this Interim Report is published in the Easter season. Both of these great festivals remind us that weakness and vulnerability are at the heart of the Christian faith. Jesus Christ was born into poverty and laid in a feeding-trough. He died as a victim of persecution himself. Given that, it is hardly surprising that many of his followers today count among the weakest and most vulnerable people on the planet. It is to them, to their needs and to their support, that this Interim Report is dedicated.

Rt. Rev. Philip Mounstephen

Bishop of Truro

Easter 2019

Overview

The Scale of Religious Persecution:

Persecution on grounds of religious faith is a global phenomenon that is growing in scale and intensity. Reports including that of the United Nations (UN) Special Rapporteur on ‘Freedom of Religion and Belief’ (FoRB) suggest that religious persecution is on the rise,1 and it is an “ever-growing threat” to societies around the world.2 Though it is impossible to know the exact numbers of people persecuted for their faith, based on reports from different NGOs,3 it is estimated that one third of the world’s population suffers from religious persecution in some form, with Christians being the most persecuted group.

This despite the fact that freedom of religion and belief is a fundamental right of every person. This includes the freedom to change or reject one’s own belief system. The UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) in Article 18 defines religious human rights in this way:

Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience, and religion; this right includes freedom to change his religion or belief, and freedom, either alone or in community with others and in public or private, to manifest his religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship, and observance. (The Universal Declaration of Human Rights)4

Despite the fact that the UDHR is foundational to the UN Charter which is binding on member states, and that ‘the denial of religious liberty is almost everywhere viewed as morally and legally invalid’, in today’s world religious freedom is far from being an existential reality.5

The Review Terms of Reference called for ‘persecution and other discriminatory treatment’ to be researched. In the absence of an agreed academic definition of ‘persecution’ the Review has proceeded on the understanding that persecution is discriminatory treatment where that treatment is accompanied by actual or perceived threats of violence or other forced coercion.

Why a focus on Christian persecution?

The final Report will include a fuller, principled, justification for the work of the Review. Significantly, it will argue that a focus on Christian persecution must not be to the detriment of other minorities, but rather helps and supports them. However, research consistently indicates that Christians are “the most widely targeted religious community”6. Furthermore, the evidence suggests that acts of violence and other intimidation against Christians are becoming more widespread.7 The reporting period revealed an increase in the severity of anti-Christian persecution. In parts of the Middle East and Africa, the “vast scale”8 of the violence and its perpetrators’ declared intent to eradicate the Christian community has led to several Parliamentary declarations9 in recent years that the faith group has suffered genocides according to the definition adopted by the UN.10

Against this backdrop, academics, journalists and religious leaders (both Christian and non-Christian) have stated that, as Cambridge University Press puts it, the global persecution of Christians is “an urgent human rights issue that remains underreported”.11 An op-ed piece in the Washington Post stated: “Persecution of Christians continues… but it rarely gets much attention in the Western media. Even many churchmen in the West turn a blind eye.”12 Journalist John L Allen wrote in The Spectator: “[The] global war on Christians remains the greatest story never told of the early 21st century.”13 While government leaders, such as UK Prime Minister Theresa May14 and German Chancellor Angela Merkel,15 have publicly acknowledged the scale of persecution, concerns have centred on whether their public pronouncements and policies have given insufficient weight to the topic. Baroness Warsi told BBC Radio 4 that politicians should set “legal parameters as to what will and will not be tolerated. There is much more we can do.”16 Former Archbishop of Canterbury Lord Carey said western governments have been “strangely and inexplicably reluctant to confront”17 persecution of Christians in the Middle East. UK Foreign Secretary Jeremy Hunt said he was “not convinced”18 that Britain’s response to Christian persecution was adequate.

There is widespread evidence showing that “today, Christians constitute by far the most widely persecuted religion.”19 Finding once again that Christianity is the most persecuted religion in the world, the Pew Research Center concluded that in 2016 Christians were targeted in 144 countries20 – a rise from 125 in 2015.21 According to Pew Research, “Christians have been harassed in more countries than any other religious group and have suffered harassment in many of the heavily Muslim countries of the Middle East and North Africa.”22 Reporting “a shocking increase in the persecution of Christians globally”, Christian persecution NGO Open Doors (OD) revealed in its 2019 World Watch List Report on anti-Christian oppression that “approximately 245 million Christians living in the top 50 countries suffer high levels of persecution or worse”23, 30 million up on the previous year.24 Open Doors stated that within five years the number of countries classified as having “extreme” persecution had risen from one (North Korea) to 11.25 Both OD and Aid to the Church in Need (ACN) have highlighted the increasing threat from “aggressive nationalism”26 or “ultra-nationalism”27 in countries such as China and India – growing world powers – as well as from Islamist militia groups. According to Persecution Relief, 736 attacks were recorded in India in 2017, up from 348 in 2016.28 With reports in China showing an upsurge of persecution against Christians, between 2014 and 2016, government authorities in Zheijiang Province targeted up to 2,000 churches, which were either partially or completely destroyed or had their crosses removed.29

Evidence shows not only the geographic spread of anti-Christian persecution, but also its increasing severity. In some regions, the level and nature of persecution is arguably coming close to meeting the international definition of genocide, according to that adopted by the UN.30 The eradication of Christians and other minorities on pain of “the sword”31 or other violent means was revealed to be the specific and stated objective of extremist groups in Syria, Iraq, Egypt, north-east Nigeria and the Philippines. An intent to erase all evidence of the Christian presence was made plain by the removal of crosses, the destruction of Church buildings and other Church symbols.32 The killing and abduction of clergy represented a direct attack on the Church’s structure and leadership. Where these and other incidents meet the tests of genocide, governments will be required to bring perpetrators to justice, aid victims and take preventative measures for the future.

The main impact of such genocidal acts against Christians is exodus. Christianity now faces the possibility of being wiped-out in parts of the Middle East where its roots go back furthest. In Palestine, Christian numbers are below 1.5 percent33; in Syria the Christian population has declined from 1.7 million in 2011 to below 450,00034 and in Iraq, Christian numbers have slumped from 1.5 million before 2003 to below 120,000 today.35 Christianity is at risk of disappearing, representing a massive setback for plurality in the region.

In its 2017 ‘Persecuted and Forgotten?’ report on Christian persecution, ACN stated: “In terms of the number of people involved, the gravity of the crimes committed and their impact, it is clear that the persecution of Christians is today worse than at any time in history.”36 Given the scale of persecution, the response of the media and western Governments has come under increasing criticism. Former Chief Rabbi Jonathan Sacks told the House of Lords: “The persecution of Christians throughout much of the Middle East, sub-Saharan Africa and Asia, [and] elsewhere is one of the crimes against humanity of our time and I’m appalled at the lack of protest it has evoked”.37 This echoes the Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem, Fouad Twal: “‘Does anybody here hear our cry? How many atrocities must we endure before someone comes to our aid?”38

Given the scale of persecution of Christians today, indications that it is getting worse and that its impact involves the decimation of some of the faith group’s oldest and most enduring communities, the need for governments to give increasing priority and specific targeted support to this faith community is not only necessary but increasingly urgent.

Types of Persecution

The persecution of and discriminatory behaviour towards Christians varies greatly in severity and intensity from place to place across every continent. It can be more or less intrusive into everyday life and its perpetrators can have varying degrees of legitimacy in local communities and national society. Oppression may come from official representatives of the state and even be enshrined in law at one end of the scale, or alternatively be the result of agitation by certain more or less informal elements within society. It can be perpetrated by close family and friends, particularly when a subject changes their religious allegiance away from that of their family, friends and neighbours. On another scale, those dissenting from the majority religion or ideology of a society can find that activities that take place in the privacy of their own home can be subject to interference and arbitrary arrest or strong social opprobrium whilst what goes on within their place of worship is largely not interfered with. Failure to belong to the majority religion or ideology of a society, especially when religious allegiance is recorded on identity papers, can also result in a limitation of access to employment and educational opportunities. The human right to freedom of religion and belief can only be said to be fully enjoyed when observance can freely take place in public and in private and when belonging to any particular religion or changing your religion or belief does not affect your life chances and opportunity for economic and social advancement in society.

Violent persecution exists in many forms. Firstly there is mass violence which regularly expresses itself through the bombing of churches, as has been the case in countries such as Egypt39, Pakistan40 and Indonesia41, whereby the perpetrators raise levels of fear amongst the Christian community and attempt to suppress the community’s appetite to practice its right to public expression of freedom of religion and belief. State militaries attacking minority communities which practice a different faith to the country’s majority also constitutes a violent threat to Christian communities such as the Kachin42 and Chin43 people of Myanmar and the Christians of the Nuba mountains of Sudan.44 The torture of Christians is widespread in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK)45 and Eritrean46 prisons, and beatings in police custody are widely reported in India.47

Extrajudicial killings and the enforced and involuntary disappearance of Christians are also widespread. These violent manifestations of persecution can be perpetrated by the state48 as has been reported by international jurists in the case of the murders taking place within DPRK prisons49 and as was allegedly seen in the kidnapping of Pastor Raymond Koh in Malaysia.50 These acts are also perpetrated by non-state actors such as Muslim extremists who systematically target and kidnap Christian girls in Pakistan51 and in the recent murder of Pastor Leider Molina in Colombia by a guerrilla/paramilitary group.52

‘Militant vigilante groups’ which ‘patrol their neighbourhoods’ looking for those who do not conform to society’s religious norms also pose a violent threat53 to Christians in India. Mob violence has become a regular occurrence in the states of Chhattisgarh, Maharashtra, Odisha, Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Jharkhand, and Telangana54 leading to beatings, forced conversion from Christianity to Hinduism, sexual violence against women and murder.55

Social persecution is often structural in nature and harder to detect, but is the type of persecution which the majority of persecuted Christians are experiencing because it is so far reaching in every area of life.56 For instance, the private lives of Christians are closely regulated in the DPRK57 with widespread state propaganda attempting to regulate the thought lives of its citizens.58 In countries such as Saudi Arabia59 and the Maldives60 citizens are not entitled to hold Christian meetings even in the privacy of their own homes. In countries such as Uzbekistan61, Turkmenistan62, Tajikistan63 and Kazakhstan64 the churches are tightly regulated with the freedom of religion and belief severely inhibited as churches are regularly raided. In both China65 and Tajikistan66 reports of churches being forced to turn minors away from services continues to undermine the right67 of parents to pass on their religion to their children.68

The suppression of public expressions of Christianity is further curbed through discriminatory behaviour and harassment by bureaucratic means.69 This includes the denial of permits and licenses which are required by law for a church to be built in countries such as Egypt.70 Beyond churches themselves, in the ‘community sphere’, government officials treating Christians with ‘contempt, hostility or suspicion’,71 on the basis of their faith, is experienced regularly with, for example, the denial of burial rights in Nepal72, the use of textbooks with contempt for non-Muslims in schools in Pakistan73, and the displacement of Christian leaders in Latin America.74 In the most extreme cases community rulings force Christians to leave their village. This type of ruling by indigenous communities in India75 and Latin America76 is regularly reported.

Finally, the situation within the ‘national sphere’ highlights the way in which Christians experience laws which are detrimental to their international right to freedom of religion or belief. According to the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom, 71 of the world’s countries have blasphemy legislation in place.77 The high profile case of the Pakistani Christian Asia Bibi highlighted that these laws are often unjustly used with accusers often lacking credible evidence.78 In other instances blasphemy legislation is used opportunistically so as to imprison Christians, as was seen in the imprisonment of the Christian Governor of Jakarta, Basuki Cahaya Purnama.79 Furthermore, unjust trials are commonplace, as has been seen in the case of Iranian Priest Ebrahim Firouzi who was originally arrested in March 2013 on allegations of ‘promoting Christian Zionism’ and has since 2015 been serving a further five year prison sentence on charges of acting against national security.80

In the ‘national sphere’, religious extremists/nationalists have carefully crafted an influential political narrative that states that Christianity is an alien or foreign religion in a number of countries.81 For example, there is a growing narrative in India that to be Indian is to be Hindu.82 Such toxic narratives, widespread amongst political elites, have led to mob violence in India83, the systematic attack of Christian minorities in Myanmar84 85and the interference with theological expression in China.86 The suppression of Christian practices under the guise of ‘anti-extremism’ legislation is also a regular tactic used to suppress church life in countries such as Tajikistan and Uzbekistan.87

Intersectionality and Freedom of Religion and Belief

In the Western mind-set FoRB is often perceived to be in opposition to other rights, notably rights around sexual identity. However there is significant evidence that a concern for FoRB actually intersects with other rights and issues that are of major concern to Western governments. Thus there is a clear intersection between poverty and social exclusion and FoRB: in Pakistan, the Christian minority is reported to be 1.6% – 2.5% of the population (2,600,000 people)88. Most live in extreme poverty, their forebears having converted from the Dalit caste before Partition.

As for poverty so for trade and security: put simply, states where FoRB is respected are more likely to be stable, and thus more reliable trading partners, and less likely to pose a security risk.

There is a particular intersection between FoRB and gender equality89. Again, put simply, in global terms if you are a Christian woman you are more likely to be a victim of discrimination and persecution than if you are a man. In the last 10 years anecdotal evidence has begun to emerge from persecuted Christians that women were suffering violent attacks, targeted abuses and restrictions because they faced what became known as double marginalisation. They were marginalised and abused because of being both a woman and Christian. Reporting on Christian women can be minimalised by the fact that they are often invisible to society and poorly represented by stakeholders and civil society. In more recent years through significant collaboration and a ground swell of interest this has changed.

In 2018 and 2019 analysis from the Open Doors World Watch list included gender profiles confirming that persecution was indeed gender specific. It correlates well with the previous reports and has validated numerous case studies that organisations such as Release International, Open Doors and Christian Solidarity Worldwide have presented in the last five years.

Thus there is strong anecdotal evidence of Christian girls being groomed and trafficked into sham marriages, often with the aim of bringing shame and dishonour on the family, in various contexts in the Middle East and from North Korea to China. In 2015 a trauma counsellor in Egypt reported that as many as 40-50% of Christians living in poverty had been victims of sexual abuse from a relative or a near neighbour who was living in close quarters. This environment perpetuates the desire for escape out of poverty and abuse, making such women particularly vulnerable to grooming.

As well as being a simple matter of justice this intersectionality of women’s rights and FoRB illustrates that Western governments, by paying attention to the latter, which has not been a traditional concern, can do much to address the former, which certainly has been a matter of significant concern to them.

Region by Region Analysis

Regional Focus: Middle East & North Africa (MENA)

The persecution of Christians is perhaps at its most virulent in the region of the birthplace of Christianity – the Middle East & North Africa (MENA for short). As mentioned earlier, forms of persecution ranging from routine discrimination in education, employment and social life up to genocidal attacks against Christian communities have led to a significant exodus of Christian believers from this region since the turn of the century.

During the past two decades religious freedom in the MENA has taken a turn for the worse.90 Sectarianism is the main source of most conflicts and remains a powerful political, social and cultural force throughout the MENA. As a result, the MENA ethnic and religious minority groups, especially Christians, face a high level of persecution by the state, by religious extremist armed groups and, in many places, by societies and communities.91 In countries such as Algeria, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Syria and Saudi Arabia the situation of Christians and other minorities has reached an alarming stage.92 In Saudi Arabia there are strict limitations on all forms of expression of Christianity including public acts of worship. There have been regular crackdowns on private Christian services93. The Arab-Israeli conflict has caused the majority of Palestinian Christians to leave their homeland. The population of Palestinian Christians has dropped from 15% to 2%.94 The 2011 uprisings and the fall of old dictatorships gave ground to religious extremism that has increased greatly the pressures upon and persecutions of Christians in Egypt, Syria, Iraq and Libya.

A century ago Christians comprised 20 percent of the MENA population. Today, they are less than 4 percent,95 an estimate of 15 million.96 Three critical factors have contributed to the drastic decline and exodus of Christians from the Middle East:

- The political failures in the Middle East have created a fertile ground for religious extremists and other actors to exploit religion, and to intensify religious and sectarian divisions in MENA. The rise of religious extremism, civil wars and general violence in various countries, especially since early 2000, has caused a huge migration of Christians (and non-Christians) from the Middle East.97 It has also impacted Muslim-Christian relationships, and compromised significantly the safety of Christians and other religious minority groups in the region.98

- MENA states such as Turkey and Algeria have become more religiously conservative. Although in many MENA countries religious minorities have been protected under Shari’a law, in reality, states do not provide equal rights and opportunities for Christians or other religious minority groups. Fighting for basic equality and rights in the market place and higher education are common challenges for many Christians in the region.

- Persecution and discrimination against Christians is not a new phenomenon in the Middle East, but it is the most important factor for the recent drastic decline of Christians from the MENA region. The rise of radical ideologies has increased religious intolerance against Christians. This can be seen throughout the MENA region.99 In countries such as Egypt and Algeria, ‘extremist groups exploit institutional weaknesses in the justice, rule of law and police system to threaten Christians.’100 The rise of hate speech against Christians in state media and by religious leaders, especially in countries like Iran101 and Saudi Arabia102, has compromised the safety of Christians and created social intolerance.

In 2016 various political bodies including the UK parliament, the European Parliament and the US House of Representatives, declared that ISIS atrocities against Christians and other religious minority groups such as Yazidis and Shi’a Muslims met the tests of genocide.103 Archbishop Athanasius Toma Dawod of the Syrian Orthodox Church called it “genocide – ethnic cleansing.”104 Whilst Release International had been informed that the numbers Christians who were killed for their faith by ISIS was not high although very large numbers were dispossessed and forced to flee, ACN argued that ‘in targeting Christians, Yazidis and Mandaeans and other minorities, Daesh (ISIS) and other fundamentalist groups are in breach of the UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide’.105

The recent defeat of the ‘Islamic State’, has strengthened the influence of other Islamist groups who continue to persecute Christians. Furthermore dramatic political changes continue to severely impact the situation of many religious minority groups, including Christians, in the region.106

MENA Trends and themes

Cases of persecution and discrimination against Christians are complex with mixed motives and multiple actors involved and vary depending on the degree of freedom of religion and belief in different countries in the region. In some cases the state, extremist groups, families and communities participate collectively in persecution and discriminatory behaviour. In countries such as Iran, Algeria and Qatar, the state is the main actor, where as in Syria, Yemen, Saudi Arabia, Libya and Egypt both state and non-state actors, especially religious extremist groups, are implicated. Christians with a Muslim background are most vulnerable and face tougher persecution from all actors and especially from their families and communities.107

As evidenced below, the most common forms of persecution, in recent years (2015 – 2018) have been martyrdom, violent threats, general harassment, legal discrimination, incitement to hatred through media and from the pulpit, detention and imprisonment.

Based on the Middle East Concern (MEC) 2018 annual report, in 2017 a total of 99 Egyptian Christians were killed by extremist groups, with 47 killed on Palm Sunday in Tanta and Alexandria. Egyptian Christians were continuously targeted by extremist groups during 2017 and 2018.

Arrest, detention and imprisonment are common in Iran, Egypt and Saudi Arabia. For example in the course of six days before Christmas 2018, 114 Christians were arrested in Iran with court cases left pending as a form of intimidation.108 Though most cases in Iran involve converts, indigenous Christians such as Pastor Victor, an Assyrian Christian, with his wife Shamiran Issavi and their son, have also been targeted and imprisoned.109

Legal obstacles that restrict the building and maintenance of places of worship are another trend in persecution and discrimination e.g. in Egypt, Algeria and Turkey. Several states such as Turkey and Algeria, have increased their interference in church institutions and leaders. Sectarian attacks against churches and church properties have also increased in Turkey and Egypt. As regards the latter, ‘sectarian tension, sometimes escalating to violent attack, [was] based on claims that Christians were using unauthorised properties as places of worship.’110 Many of these properties had in fact been used for Christian worship for years, with permit applications pending for substantial periods without response.

Confiscation of church properties, attack on churches and properties owned by Christians in Syria, Iran,111 Egypt and Algeria have been reported.112 Community-based sectarian attacks on church properties have increased in Egypt, Turkey and Israel, including vandalism of churches.113 Similar attitudes are demonstrated in the northern area of Cyprus currently under Turkish occupation. Access for worship to the historic Orthodox and Maronite churches in the area is severely restricted (only once a year if specific permission is granted in many cases) and even in the small number of churches where regular Sunday services are permitted intrusive police surveillance114 is complained of and services may occasionally be closed down by force and the congregation evicted without notice. Other churches are able to worship weekly but also complain of intrusive police surveillance. Many historic churches and associated cemeteries in the area have also been allowed to fall into disrepair, be vandalised or converted to other uses115.

Incitement to hatred and hate propaganda against Christians in some states, and by state sponsored media and social media, especially in Iran, Iraq and Turkey, have escalated. The governing AK Party in Turkey depicts Christians as a “threat to the stability of the nation.116” Turkish Christian citizens have often been stereotyped as “not real Turks” but as Western collaborators. Turkey’s Association of Protestant Churches in their 2018 annual Rights Violation Report claimed that anti-Christian hate speech had increased in the Turkish media including private media.117” During the Christmas 2017 and New Year 2018 season various anti-Christmas campaigns were carried out; the Diyarbakir protestant church was stoned, and antagonistic posters were hung on the streets. “The participation in these campaigns by various public institutions created an intense atmosphere of hate.”118

Similarly, the US Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF) issued a study of Saudi school textbooks in March 2018. The findings confirmed that they teach pupils religious hatred and intolerance towards non-Muslims “including references to anti-Christians and anti-Jewish bigotry.”119 Throughout 2017, according to MEC, threats to Christians in Iraq, in areas dominated by Shi’a militia increased. Christians coming from a Muslim background have been the most vulnerable in almost all states in the MENA region. Their perpetrators have mainly been extremist groups and their own family and community members, except in Iran in which the state is the main persecutor of Christians.

Due to lack of trust in the security system, and the extended damage to their homes, only a modest number of Christian refugees have returned to their homelands in Iraq and Syria. Since the impact on Christians of the ongoing crisis in Syria has remained disproportionately high, Christian communities are heavily concentrated in government-controlled areas or in the North East.

Discrimination in employment and higher education, especially for Christian converts, is very common, and most of such discrimination goes unreported and unchallenged. Though Christians in Jordan to some extent enjoy freedom, most of the persecution has targeted Christians from a Muslim background.

In Kuwait, Bahrain, Oman and UAE Christians are relatively free to worship as long as they obey the state’s restrictions and do not evangelise Muslims. Qatar allows foreign churches, but restricts the importation of Bibles.120

MENA – Conclusion

Religious persecution and discrimination, political failures, the rise of Muslim extremists, and the lack of legally protected freedom of religion and belief have all contributed in shaping the status of Christians in the MENA region. Based on Pew Research findings, Christians remain the most persecuted and vulnerable of religious groups in the Middle East (and around the world).121 Though the decline of Christians from the Middle East started in the early 20th century, during the past decade, on the evidence cited above, millions of Christians have been uprooted from their homes, and many have been killed, kidnapped, imprisoned and discriminated against.

Despite the disheartening nature of the situation, the steadfast presence of Christians in the region is a sign of hope and opportunity to advocate for religious protection, to advance pluralism and religious tolerance across the region as well as preserving Christian heritage, fostering positive relationships between Muslim and Christian communities, and encouraging peace and reconciliation.

Regional Focus: South Asia

To the east of the MENA region lie countries with a diversity of majority religions. In nearly all of these there is routine discrimination against Christians which has crossed over into outright persecution in recent years.

The growth of militant nationalism has been the key driver of Christian persecution in the south Asia region. In a number of cases – although by no means all – nationalistic ambitions have been yoked to a specific religion to which Christianity is perceived as being threatening or antagonistic. According to one analysis, ‘A number of political parties in the region have outwardly embraced militant religious causes to increase their populist electoral base, exploiting the issue of religion at the expense of their opponents. This is the case in India (with the Bharatiya Janata Party), Pakistan, and Bangladesh.’122 One might also add Sri Lanka’s Jathika Hela Urumaya, a Sinhalese nationalist party, in which Buddhist monks have been active from its formation. In countries such as Pakistan, India and Sri Lanka extremist forms of Islam, Hinduism and Buddhism have increasingly flexed their muscles.123 Ahmed Shaheed, the UN’s special rapporteur for religious freedom, identified an increase in religious fundamentalism as leading to religious liberty being “routinely violated across much of Asia.”124

Christians were already marginalised socially especially where ‘employment opportunities, welfare assistance, social networking were shaped by ethno-religious ties’.125 However, the rise of militant nationalism has been accompanied by a substantial rise in the number of attacks. Without reducing and homogenizing the drivers of these incidents, it is fair to say that the nationalistic, mono-religious impulses mentioned above are often a significant factor in such incidents. In 2017, Sri Lanka saw a rise in attacks on both Christians and Muslims, with 97 documented incidents, despite violent incidents against Christians having fallen after a previous peak. These included ‘attacks on churches, intimidation and violence against pastors and their congregations, and obstruction of worship services’.126 In India, persecution has risen sharply since the rise to power of the right-wing Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi in 2014.127 Figures suggest that there were 736 attacks against Christians in 2017, compared with 358 in 2016.128

It is worth noting at this point that in South Asia, as elsewhere, Christianity often acts as a bellwether for the state of freedom of religion and belief more generally, and the problems affecting Christians will almost invariably reflect the sorts of issues facing other minority religious groups. While data is available marking the rising number of attacks on Christians in India, unfortunately no comparable figures exist for attacks on the country’s other groups. However, there is evidence indicating that attacks on other minority religions, including the country’s Muslim community, also rose during the same period.129 This further reinforces the point that Christian persecution provides a bellwether for the general state of religious liberty and the toleration of minority religious groups in the region.

Allied to rising attacks are reports of Christians being denied redress under the law, regardless of their constitutional, statutory or other legal rights. There have been reports of police failing to respond to incidents in countries across the region. The Rt Rev’d Anthony Chirayath, Syro-Malabar Bishop of Sagar, central India, described Hindutva extremists beating up eight of his priests and burning their vehicle in Satna, Madhya Pradesh. No action was taken by the authorities, despite the incident happening outside a police station.130 In Pakistan, police refused to start an investigation after Arif Masih and his sister, Jameela, were seized by seven men with guns and rods who burst into the family home near Kasur in September 2016. After beating members of the Christian family, the intruders dragged 17-year-old Jameela and 20-year-old Arif into a van parked outside the home. After Arif finally escaped from the large house the siblings were taken to, he described hearing his sister screaming and reported being told that men were taking turns to rape her, but that this would stop if he converted to Islam.131 The kidnapping of girls from Christian and indeed other religious minority backgrounds is a significant problem in both Pakistan and India,132 one that reports suggest is exacerbated by the authorities’ reluctance to take action in both countries.

Restrictive legislation can cause problems for Christians and other minority groups. In November 2018 the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF) called on the U.S. government to press governments in Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka to rescind anti-conversion laws, ‘that limit the ability of religious groups to proselytize and the freedom of individuals to convert to a different religion’. 133 In a report issued at the same time the commission stated:

Often the motivation behind these laws, though not officially stated as such, is to protect the dominant religious tradition from a perceived threat from minority religious groups. The methods of preventing conversion vary: in India, several state legislatures have adopted laws limiting conversions away from Hinduism; in Pakistan, national blasphemy laws are used to criminalize attempts by non-Muslims to convert Muslims; and in India, Pakistan, and Nepal, governments are tightening their control over non-governmental organizations (NGOs), especially foreign missionary groups.134

While one should not ignore genuine concerns that such groups may be using aggressive and manipulative forms of proselytism most mainstream Christian groups strongly eschew such methods.135 However, claims of this sort of behaviour feed into narratives of Christianity as intrinsically antagonistic to the majority faith group. In India BJP MP Bharat Singh described Christian missionaries as ‘a threat to the unity of the country’.136 In Nepal, where evangelisation is prohibited by constitution, six Christians in the eastern Tehrathrum district were placed under police custody on charges of evangelising in May 2018. Two of them were arrested while singing worship songs in public and four others were taken from their home by police.137

While a number of countries in the region have blasphemy laws, in many countries such as Sri Lanka, India and Indonesia, these are framed in general terms and, at least in theory, offer equal protection to all religious groups.138 However, the USCIRF notes that Pakistan’s laws in this area are notable for their ‘severity of penalty’.139 Under articles 295 B, 295 C, 298 A, 298 B, 298 C of the Pakistan Penal Code profaning the Qur’an and insulting Muhammad are both punishable offences, respectively carrying maximum sentences of life imprisonment and death.140 The reach of Pakistan’s blasphemy laws affects all non-mainstream-Muslim minority groups, including Ahmadi Muslims, Hindus, Sikhs and humanists.141 The most notorious case was that of Asia Bibi, a Christian woman who spent ten years in jail after being sentenced to death for blasphemy. Despite being released from prison in late 2018, she was at the time of writing still reportedly living in hiding, fearing that vigilante mobs would carry out the original court sentence. Mobs often take the law in their own hands following blasphemy accusations. A number of those accused of blasphemy have been killed before the case reaches the courts.

South Asia: Conclusion:

The growth of militant nationalism has been the key driver of Christian persecution in South Asia. The table below encapsulates the range of measures used to limit minority rights in the region.

Summary of Majoritarian Limits Used to Prevent Religious Conversion in South Asia

(USCIRF data from Limitations on Minorities’ Religious Freedom in South Asia, p.2) |

| Country |

Bangladesh |

India |

Nepal |

Pakistan |

Sri Lanka |

| Majority Religious Group |

Muslim

(86%) |

Hindu

(80%) |

Hindu

(80%) |

Muslim

(96.5%) |

Buddhist

(70%) |

| Impacted Minority Religious Groups |

Christian, Hindu

(12.5%) |

Christian, Muslim

(16.5%) |

Christian, Muslim

(6%) |

Christian, Hindu

(3.5%) |

Muslim, Christian

(17.3%) |

| Existence of Anti-Conversion Laws |

N |

Y |

Y |

N |

Law Proposed, invalidated in 2004 |

| Existence of Blasphemy Laws |

N |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

| International NGO Registration Limitations |

Y |

Y |

New Law Proposed in 2018 |

Y |

N |

In a new development for Sri Lanka the specific targeting of Catholic and Protestant Christians appears to be the motivation for the horrific 2019 Easter bombings, as part of the wider ISIS inspired Jihadist movement with the perpetrators stating their allegiance in a pre-recorded video message to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi142. This attack combined the targeting of Sri Lanka’s Christian minority with western tourists and visiting members of the Sri Lankan diaspora (some of whom were eating breakfast, having recently returned from Easter vigils at local churches) as the prime focus of the attacks.

Regional Focus: Sub-Saharan Africa

To the south of the MENA region lies sub-Saharan Africa. It is, overwhelmingly, a majority Christian region. However, a string of countries on the southern edge of the Sahara desert, roughly from Dakar to Djibouti have formed a fault line where Muslim-majority culture and Christian-majority culture abut and overlap. Inter-communal tensions that have been limited in the past have come under severe pressure from extremist groups triggering violent attacks and discriminatory actions.

Some of the most egregious persecution of Christians has taken place in Sub-Saharan Africa, where reports showed a surge in attacks during the period under review.143 Evidence from across the region points to the systematic violation of the rights of Christians both by state and non-state actors. While the 2014-19 period saw renewed government crackdowns on Christians in some countries, notably Eritrea, the most widespread and violent threat came from societal groups, including many with a militant Islamist agenda.144 The most serious threat to Christian communities came from the militant Islamist group Boko Haram in Nigeria, where direct targeting of Christian believers on a comprehensive scale set out to “eliminate Christianity and pave the way for the total Islamisation of the country”.145 Extremist Muslim militancy was also present in other countries in the region, including Tanzania146 and Kenya, where Al Shabaab carried out violent attacks on Christian communities. Elsewhere, extremist groups exploited domestic conflicts and unrest in countries such as Somalia147 where violence against Christians took place against a backdrop of popular uprisings, economic breakdown and endemic poverty. The threat to Christians from Islamist militancy was by no means confined to societal groups. Sudan continued to rank as one of the most dangerous countries for Christians;148 destruction of church property, harassment, arbitrary arrest initiated by state actors remained a problem and non-Muslims149 were punished for breaking Islamic Shari‘a law.

Reports consistently showed that in Nigeria, month after month, on average hundreds of Christians were being killed for reasons to which their faith was integral.150 An investigation showed that in 2018 far more Christians in Nigeria were killed in violence in which religious faith was a critical factor than anywhere else in the world; Nigeria accounted for 3,731 of the 4,136 fatalities: 90 percent of the total.151 The single-greatest threat to Christians over the period under review came from Islamist militant group Boko Haram, with US intelligence reports in 2015 suggesting that 200,000 Christians were at risk of being killed.152 The extremist movement’s campaign was not just directed against Christians but towards all ’political or social activity associated with Western society‘153, with attacks on government buildings, markets and schools. That said, Christians continued to be a prominent target. Those worst affected included Christian women and girls ‘abducted, and forced to convert, enter forced marriages, sexual abuse and torture.’154 In 2014, Boko Haram kidnapped 276 school girls from Chibok, a mainly Christian village. A video released later purported to show the girls wearing Muslim dress and chanting Islamic verses, amid reports that a number of them had been “indoctrinated” into Islam. In the video Boko Haram leader Abubakar Shekau warns of retribution for those who refuse to convert, adding: ’we will treat them… the way the prophet treated the infidels he seized.’155 In its 2018 report on Nigeria, the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom described how Boko Haram had ’inflicted mass terror on civilians‘, adding: ‘The group has killed and harmed people for being “nonbelievers”‘.156 In Maiduguri city, north-east Nigeria, Catholic Church research reported that massacres by the Islamists had created 5,000 widows and 15,000 orphans and resulted in attacks on 200 churches and chapels, 35 presbyteries and parish centres.157 A Boko Haram spokesman publicly warned of an impending campaign of violence to eradicate the presence of Christians, declaring them ’enemies‘ in their struggle to establish ’an Islamic state in place of the secular state‘.158 Evidence of intent of this nature combined with such egregious violence means that Boko Haram activity in the region meets the tests for it to be considered as genocide against Christians according to the definition adopted by the UN.159

The precise motives behind a growing wave of attacks by nomadic Fulani herdsmen in Nigeria’s Middle Belt has been widely debated, but targeted violence against Christian communities in the context of worship suggests that religious hatred plays a key part. On 24th April 2018, a dawn raid, reportedly by Fulani herders, saw gunmen enter a church in Benue State, during early morning Mass and kill 19 people, including two priests.160 On April 18th 2019 in a detailed account it was reported that on Sunday April 14th Fulani herdsmen killed 17 Christians, including the mother of the child, who had gathered after a baby’s dedication at a church in an attack in Konshu-Numa village, in Nasarawa state’s Akwanga County in central Nigeria.161

Attacks on Christians by Muslim extremist groups took place on a lesser scale in other parts of Sub-Saharan Africa, notably Tanzania and neighbouring countries. In Kenya, 148 people were killed when Al Shabaab militants carried out an attack at Garissa University College. Witnesses stated that heavily armed extremists singled out Christians and killed them.162

Evidence indicated that the Al-Shabaab threat in Kenya had emanated from neighbouring Somalia.163 Here, as was the case in other parts of Sub-Saharan Africa, long-term widespread internal conflict and endemic poverty had incubated a form of religious extremism specifically intolerant of Christians. In 2018, Catholic sources on the ground in Mogadishu, the Somali capital, stated that Christians there were living underground for fear of attacks from militants164 and in July 2017 Somaliland authorities closed the only church in Hargeisa.165 With reports citing the existence of Daesh (ISIS) cells in Somalia, extremist militants were accused of being behind a video, released in December 2017, calling on militants ‘to “hunt down” the non-believers and attack churches and markets.’166

Reports indicate that such attacks on Christians were unprovoked. In countries beset by significant internal conflict such as the Central African Republic, the role played by Christians was less clear. In CAR, widespread attacks – perhaps even “early signs of genocide”167 – against Muslims were carried out by anti-Balaka militants. Reports indicated that the militants styled themselves as ‘defending‘168 Christianity but CAR Church leaders have repeatedly repudiated the notion that anti-Balaka should be characterized as “a Christian group”, pointing to the presence of animists amongst them.169 Attacks on Christians in CAR by ex-Seleka militants were reportedly carried out in defence of Muslims, nonetheless many innocent Churchgoers were targeted.170 In Mali, a peace settlement, which followed the 2013 ousting of Islamist militants, did not pave the way to a complete restoration of law and order. Clergy reporting on the situation in northern Mali described sporadic suicide bomb incidents, but said that there were no specific attacks against Christians.171 However, other reports, including from the south of the country, did describe deliberate targeting of Christians by extremists.172

Elsewhere in Sub-Saharan Africa, responsibility for the persecution of Christians lay with the state. In Sudan, ’the Sudanese government continued to arrest, detain and prosecute Christian leaders, interfere in church leadership matters and destroy churches‘.173 Evidence suggests that since the secession of the south to form South Sudan in 2011, the Khartoum government has increased its clampdown on Christians.174 Over the next six years, 24 churches and church-run schools, libraries and cultural centres were reportedly ‘”systematically closed”, demolished or confiscated on government orders.’175

Other countries with an explicitly Islamic constitution and government also denied Christians their basic rights. In Mauritania, where ’no public expression of religion except Islam was allowed‘,176 foreign worshippers were allowed to worship in the country’s few recognised Christian churches. In a country where ‘citizenship is reserved for Muslims‘,177 a group of Protestants applied for a place of worship back in 2006 and 12 years later had still not succeeded in spite of two subsequent attempts to win government approval for their plans.178

In Eritrea, non-registered Christian groups bore the brunt of government-sponsored religious persecution. A 2016 UN human rights commission found that attacks on unauthorised religious groups including Protestants and Pentecostals ‘were not random acts of religious persecution but were part of a diligently planned policy of the Government.’179 In a country where the regime is suspicious of faith groups as focal points of foreign-inspired insurrection movements, Pentecostals and Evangelicals ‘comprise the vast majority of religious prisoners’.180 Following a rare fact-finding visit to the country by Catholic charity Aid to the Church in Need, reports emerged of nearly 3,000 Christians imprisoned – with many of them ‘packed‘ into metal shipping containers.181 The government reportedly arrested about 210 evangelical Christians in house-to-house raids throughout the country as part of a renewed clampdown on unregistered Churches.182 There were persistent concerns about the fate of Eritrean Orthodox Patriarch Abune Antonios, deposed by the regime in 2006, put under house arrest and not seen in public for more than a decade.183

Regional Focus – East Asia region

This regional overview brings together two of the world’s regions: South East Asia (focusing on Laos, Myanmar, Vietnam, Philippines, Brunei, Malaysia and Indonesia) and East Asia (focusing on China and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK)).184 For the purposes of this overview ‘East Asia’ is used as a catch-all term. Apart from the Philippines, where persecution is only concentrated in the south of the country,185 each of these countries consistently appear on Open Doors’ World Watch List – a ranking that outlines the 50 countries in the world where it is most dangerous to be a Christian. There are extensive levels of persecution in East Asia as a whole. DPRK has consistently registered for the past 18 years as the most dangerous country in the world for Christians; significant numbers of Christians in China are at risk of persecution, and persecution in South East Asia has for two years running been highlighted as a ‘trend’ and ‘region to watch’ in Open Doors UK’s annual World Watch List report186.

The countries under study in this overview all share similar drivers of persecution. This includes persecution by the state, manifested through both communism (specifically seen in DPRK, China, Laos, Vietnam) and nationalism (specifically seen in Bhutan and Myanmar) and Islamic militancy – both through the state (as is seen in Indonesia, Malaysia and Brunei) and as a wider force within civil society (in Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines). Likewise, Buddhist nationalism is also a force within civil society in Myanmar.

Authoritarianism, communism and nationalism

State authoritarianism is a key driver of the persecution of Christians in East Asia with a number of states in the region suspicious of Christianity and in many cases viewing the religion as foreign and deviant. For instance, the closed state of DPRK acts ruthlessly towards Christians who are seen to act in contrast to the state’s ‘Juche ideology’ which refuses to tolerate any other belief or religious system.187 North Korea’s ‘Songbun’ social stratification system determines who gets access to food, education and health care based on people’s position in one of 51 potential categories, which signify greater or lesser loyalty to the regime. Those in lower categories, including Christians, are considered hostile to the state.188 Citizens of the DPRK live under heavy surveillance, with the state’s National Security Agency co-ordinating efforts to ‘uncover reactionary elements’ and ‘anti-government’ forces. Christians are found within this category, along with spies and political dissidents.189 In fact, spying on behalf of the West is a common accusation made against Christians in DPRK.190

DPRK’s constitution states that citizens have freedom of religion as long as it does not attract foreign intervention or disrupt the state’s social order. It is in light of this that the state ties Christian belief to the West and particularly the United States of America as a way of indicating that Christianity is a national security risk.191 In reality the right to freedom of religion or belief in DPRK is non-existent.192

The risks involved in practising Christianity in DPRK means that it is almost entirely practised underground.193 A former security agent interviewed by Open Doors noted that he was trained to recognise religious activity and to organise fake ‘secret’ prayer meetings so as to identify Christians.194 When Christians are discovered they experience intense interrogation which normally includes severe torture, imprisonment or even execution.195 Those who are imprisoned have reported horrific acts taking place while in custody such as violence, torture, subsistence food rations and forced labour resulting in high death rates.196 Some have argued that the acts of egregious violence carried out against citizens within these prisons amount to crimes against humanity.197

The Chinese government forcibly returns Christians who flee the country, openly violating the international principle of non-refoulement.198 There is evidence that those returning to DPRK from China are tortured, and if there is evidence they engaged with Christians or churches across the border, or if a Bible is discovered on their person, they will likely face life imprisonment or execution.199 A report by the UK All Party Parliamentary Group on Freedom of Religion or Belief highlights the case of a female deportee who was found with a Bible on her return from China. A witness reported that, as soon as the Bible was discovered, the deportee disappeared from the detention centre in which she was being held.200

When it comes to China’s own citizens, its communist ideology and nationalistic outlook leads it to suppress the Christian church in a number of ways. The Communist party in China has historically attempted to limit freedoms throughout Chinese society so as to maintain a strong grip on the country and to ensure it stays in power.201 In recent years President Xi has sought to control the church.202 As part of this, the Chinese state has provided ‘active guidance’ for Chinese churches to adapt to China’s socialist society203 and legislation came into force in February 2018 which gave the state far-reaching powers to monitor and control religious organisations.204 While article 36 of the constitution gives protection to all ‘normal’ religious activity,205 this only extends to religious organisations registered with state-sanctioned religious associations.206 Churches which register with the state and hence become state sanctioned (i.e. ‘Three Self’ churches and the ‘Chinese Catholic Patriotic Association’) are expected to compromise heavily on their right to freedom of religion or belief by removing religious symbols, singing patriotic pro-Communist songs and flying the national flag. Churches which refuse to register with the state (for instance ‘house churches’) have come under great pressure to close and experience surveillance, intimidation, fines and their leaders are regularly detained.207

Accusations against, and arrests of, Christians in China take on subtle forms, with Church leaders accused of embezzlement and fraud as a way of impeding their ministry.208 Churches have also been requested by authorities to remove religious symbols from buildings in Henan province209. Likewise, churches have been demolished and confiscated in Zhejiang and in other regions of the country.210 Concerns over the freedom to sell Bibles online were also reported in 2018.211

In a wide-ranging resolution of 18 April 2019 the European Parliament noted China’s hostility to a number of minorities and noted that “Christian religious communities have been facing increasing repression in China, with Christians, both in underground and government-approved churches, being targeted through the harassment and detention of believers, the demolition of churches, the confiscation of religious symbols and the crackdown on Christian gatherings”. It further called “on the Chinese authorities to end their campaigns against Christian congregations and organisations and to stop the harassment and detention of Christian pastors and priests and the forced demolitions of churches” and “to implement the constitutionally guaranteed right to freedom of religious belief for all Chinese citizens.”212

Christians in Laos and Vietnam experience similar suppression by their states (which are likewise influenced by Communist ideologies) as do Christians in Bhutan. Churches in Vietnam, Laos and Bhutan are expected to register with the state so as to receive permission for church meetings.213 In the case of Vietnam and Laos, human rights organisations have noted that those which refuse to register, or have their registration refused, are subject to harassment, intimidation and violence. These churches have had their property seized and members have had their homes destroyed.214 For instance, in June 2016 authorities disrupted a Catholic prayer service held in a parishioner’s home in the Lao Cai province, with security agents reportedly assaulting some of those attending the meeting and confiscating the phones of those trying to record the incident.215 The Montagnard ethnic minorities, many of whom practise Christianity and are located in the Vietnamese central highlands, also experience severe violations because of their perceived difference.216 Indeed, the organisation Human Rights Without Frontiers has noted that the Montagnard community are perceived as a threat to the national integrity and security of Vietnam in which the majority religion is Buddhism.217 In Bhutan Christians have informal meetings closed down by authorities in rural areas.218 Christians in Bhutan have also been refused the right to bury their dead, despite requesting that the government provides allotted burial sites for the community.219

In Laos, Christianity is regularly framed as a ‘foreign religion’ which is at odds with Laos’ traditional culture and this has led to Christians being arrested for explaining the Bible to individuals of other religions.220 Indeed, framing Christianity as the ‘other’ or ‘alien’ and therefore a religion which is out of bounds to citizens of the country is a wider phenomenon across the region. For instance, in Myanmar and Bhutan, both state and societal actors persecute non-Buddhists on the basis of their religious difference. The systematic targeting of the majority Christian Kachin and Chin communities by Myanmar’s state army is undoubtedly both an ethnic and religious issue with evidence that the army has specifically targeted and destroyed the communities’ churches and attempted to convert Kachin people to Buddhism through coercive measures such as denying the community access to education.221

However, Buddhist nationalism as a driver of persecution of Christians is not limited to the state in Myanmar. For instance, research conducted by the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom in the Chin, Kachin and Naga regions of Myanmar has documented that both the state and extremist Buddhist monks have been acting in a discriminatory fashion towards Christians by restricting land ownership, intimidating and acting violently towards the Christian communities and by attacking Christian places of worship and cemeteries. An ongoing campaign of coerced conversion to Buddhism has also been reported.222 In 2018 Human Rights Watch reported the destruction of homes and property as a Buddhist mob attacked Christian worshippers in the Sagaing region of the country.223 The Christians living in the Shan region of Myanmar have also been targeted on the basis of their faith by the rebel United Wa State Army224 who have run a systematic campaign of church closures in the region.225

Islamic Militancy

The growing influence of Islamic militancy within the state and society at large is a key driver of the persecution of Christians in the region, leading to Christians being harassed, having their space for religious practise curtailed and in the worst cases egregious acts of violence perpetrated against them.

There are a number of laws in Indonesia, Malaysia and Brunei which undermine the rights of minority religions and create an environment of hostility for those who do not practise Islam. For instance, in Indonesia, the implementation of discriminatory laws and regulations such as blasphemy legislation226 and Shari’a-inspired regulations as well as restrictions on church construction undermine the international right to freedom of religion or belief in the country. CSW has argued that Indonesia’s blasphemy legislation is used to silence dissent, criticism and debate in the country with the blasphemy law’s low threshold for proof of intent resulting in it easily being used by Islamic militants looking to silence those with whom they disagree.227 This was undoubtedly the case with blasphemy accusations made against Basuki Purnama (or ‘Ahok’), the former governor of Jakarta and Christian of Chinese descent. With little credible evidence, Puranama was accused of blasphemy for stating that his political opponents were using Quranic verses to stop Muslims from voting for him.228 There is no doubt that the accusations were an attempt to derail his bid for re-election as governor of the city.229

Similarly worrying are laws such as Penal Code 298 in both Malaysia and Brunei which makes ‘uttering words etc, with deliberate intent to wound religious feelings’ illegal.230 Once again, this vague and ill-defined language opens up the opportunity for the law to be misused. Brunei also reserves the use of the word Allah for certain contexts and tightly regulates church construction and permits.231 By decree the import of Bibles and Christmas celebrations are banned in Brunei.232 Malaysia’s definition of ethnic Malays as Muslims also undermines the rights of converts in Malaysia. That Muslims may proselytise within Malaysian society, but other religions may not, is also concerning. Furthermore, the probable involvement of the Malaysian special branch in the abduction of Pastor Raymond Koh, as announced by the Human Rights Commission of Malaysia in April 2019,233 suggests a connection between state agents and anti-Christian sentiment in Malaysia. Koh had been accused by the Selangor Islamic Religious department of trying to convert Muslims to Christianity in 2011 and hence there is reason to believe the abduction was religiously motivated.234

Beyond the state, Islamic militancy is also becoming a growing problem for Christians within society at large. Evidence that Indonesia’s education system has been infiltrated by extremist Islamic thinking has been shown by one report which indicates that 60% of the country’s teachers are intolerant of other religions.235 Furthermore, Indonesia’s President Widodo’s choice of ultra-Islamic cleric Ma’ruf Amin as his running mate for the 2019 elections236 highlights how public opinion in Indonesia has shifted in recent times. Indeed, the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom has noted the growing politicisation of religion in Indonesia.237 The bombing of three churches in Surabaya in May 2018 by members of one family, thought to have links to the Daesh inspired Jemaah Ansharut, particularly highlights how dangerous the infiltration of Islamic extremism into Indonesian society has become.238 Likewise, the siege of the southern Philippines city of Marawi by Islamic militants in 2016, which led to Christians being held hostage239, plus the bombings outside a church in Mindanao in 2016240 and of a church in Jolo in January 2019,241 with the perpetrators thought to be Islamic militants, indicates that extremist Islam is an ever-real threat in the majority Christian nation of the Philippines. This highlights the extent to which Islamic militancy is a severe issue right across the region.

East Asia Conclusion

This overview has demonstrated how the extensive persecution of Christians across the East Asia region is driven both by the authoritarian actions of governments influenced by communist and nationalist outlooks and by Islamic militancy found both within the state and within civil society. Ideologies which aim to ensure complete control and which turn the ‘other’ into deviants are prevalent across the region, leading to high levels of persecution.

Regional Focus – Central Asia region

Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Turkmenistan are often known collectively as Central Asia and treated as one region. Azerbaijan and Afghanistan are also on occasion viewed as part of the region, due to cultural and political similarities.242 For the purpose of this Review, we consider all seven countries part of Central Asia.

Central Asia Introduction

With the exception of Afghanistan, leaders of Central Asian countries tend to have come out of the Communist party of the Soviet era.243 Their authoritarian governments reflect the policies and methods of the Soviet era with regard to religious discrimination and intimidation. All religions have been repressed and kept away from the public sphere.244 The states perceive religious communities including Christians “a threat and challenge to their legitimacy.”245 Thus, authoritarian governments maintain tight controls over freedom of religion and expression.246

Christian persecution and discrimination is on the rise in Central Asia, as elsewhere in the world. Several NGOs and governmental bodies have voiced their concerns, including Release International,247 Open Doors,248 Forum 18,249 as well as Human Rights Watch250 and the US Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF).251 In 2018 Release International launched a campaign on behalf of persecuted Christians and churches in Central Asia to raise awareness of the Christian situation there252 and to help the persecuted Christians in the region.253

Apart from Kyrgyzstan, all countries have been listed in the Open Doors World Watch list among the 50 countries in which Christians face the most persecution.254 The 2018 annual report of USCIRF listed Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan among Countries of Particular Concern (CPC). Afghanistan, Azerbaijan, and Kazakhstan were not far behind: they were listed among the Tier 2 Countries, with regard to the seriousness of the states’ violations of religious freedom and human rights.255

Christian persecution in Central Asia comes in many forms. The most extreme is the criminalisation of Christianity.256 Security police in Tajikistan arrested and fined ten Christians in August 2018 for handing out gospel literature. In Kazakhstan, in 2017, Pentecostal and Protestant churches faced a total ban on religious activities for three months and this continued into 2018. Within a period of around six months 80 Christians were prosecuted.257 In Turkmenistan Christian women from Muslim background were kidnapped and married off to Muslims. In most Central Asian states, parents are not allowed to take their children to the church or any religious activities. In Turkmenistan Christian prisoners have faced torture, with the police calling their techniques “the Stalin principles”.258

Added to this, in recent years, to prevent the rise of Islamic extremism, the Central Asian governments have further toughened their laws and regulations against religion. Their “anti-extremist” legislation has caused more pressure on ordinary believers. For instance, a Presbyterian pastor from Grace church in Kazakhstan was arrested in 2015 for “causing psychological harm” to church members: he was released later that year, then rearrested as a terrorist on charges of extremism.259

Despite heavy restrictions on religion, Islamic militancy is on the rise in all states of Central Asia. ISIS also recruited some of their fighters from Central Asian states.260 In Tajikistan, Islamic groups are spreading mainly due to poverty and the influence of Iran on Tajik society.

Although the states are the main perpetrators of persecution of Christians, the rise of religious extremism has also increased societal persecution, especially against Christians from a Muslim background. Thus, “Christianity in Central Asia represents an exceptional case: they have conjoined a soviet experience of militant state atheism and that of being a religious minority within Muslim space.”261

The situation of Russian Orthodox and Catholic churches appears to be better than that of Protestant churches, both as the result of the influence of Russia and the fact that the Central Asian states view non-Russian Orthodox Christians as potential Western spies, “who are presumed to be orchestrating anti-regime activity.”262

Contrary to other Central Asian states, the Afghan government is not the main oppressor of Christians, it is rather the Taliban, and other religious extremist groups and society. The state does not require religious communities to register.263 Religious education is not banned and non-Muslims are not required to study Islam in public schools.264

Christians in Central Asia

Islam is the majority religion in all countries of Central Asia. The precise number of Christians in each country is unknown for two reasons: firstly, for political reasons Central Asian governments conceal the correct population of Christians. Secondly, Christians from a Muslim background, for fear of persecution, keep a low profile and do not register themselves as Christians or as members of a church. Nevertheless, the Christian population varies in each country. Based on the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA)’s World Factbook, Uzbekistan’s Christian population is estimated at 12 percent: 9 percent Russian Orthodox, and 3 percent other Christian denominations.265 Tajikistan has a Christian population of less than 2 percent. Christians in Kyrgyzstan comprise 10 percent, and in Turkmenistan, they number 9 percent of the population. Kazakhstan has the highest Christian population in Central Asia with over 26 percent.266 Azerbaijan’s Christian population is between 3-4 percent. Afghanistan has a small group of Christians mainly from a Muslim background: their number is unknown. In general, moving towards the north the number of Christians increases, due to the estimated seven million Russian Orthodox Christians from Russia and Ukraine who still live in Central Asia.267 Christian communities also include Catholics, Evangelical and Pentecostal Churches. Jehovah’s Witnesses are also present.

There are no church buildings in Afghanistan. The small population of Christians worship in private and in secret. Although there is no penalty assigned to conversion from Islam, the Afghan constitution states that where there is no provision in the constitution for a legal case, the judgement can be drawn from the Sunni Islam Hanafi School of Jurisprudence. According to the Hanafi School, conversion from Islam to another religion is considered apostasy and punishable by death, imprisonment and confiscation of properties. Thus Christian converts from Islam fear persecution, not only from the state but also from family and society.268 The U.K.’s All Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) for International Freedom of Religion or Belief found that in Afghanistan while ‘specific violations against Christians are rarely reported because of security issues… killings of converts… continue’.269 The APPG concluded that ‘a lack of reporting has tended to give the impression that violence against Christians is not taking place in Afghanistan, at times leading to a misunderstanding that it is safe to return Christian converts to the country’.270

Central Asia Persecution Trends