Monthly Archives: December 2022

One Hour of Soviet Communist Music – CCCP – 30 Dec 1922 – Requiescat In Pace Et In Amore

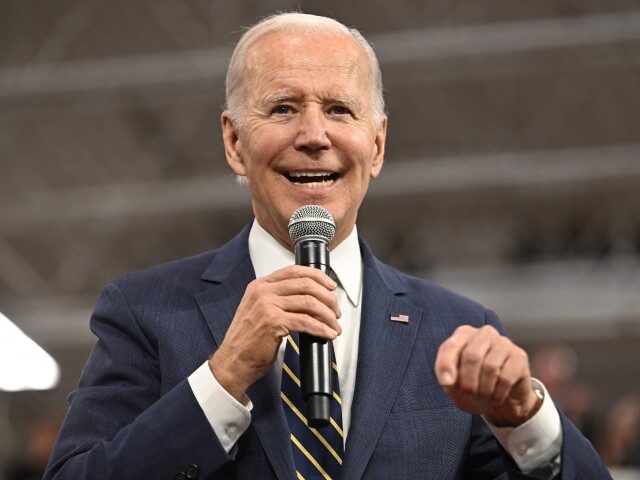

Pulitzer Prize in Fiction Nominee – Biden’s Top 15 ‘Stories’

President Joe Biden has told a lot of ‘stories’ before and during his presidency. Here are the top 15 most outlandish lies from his career.

(cont. https://archive.ph/9F6sX )

We – 1921 Rus Novel – Gets Me Banned Again – Audio Book (6:30:00 min)

Decades passed as this book sat among my books. Moved here, there, one state to another. I had a vague idea of the plot, or maybe I had simply read the back cover. The novel depicted a future ‘scientific’ society that was a nightmare. When I was in high school the dystopian works were read and discussed. Orwell’s ‘1984’ and ‘Brave New World’ from Huxley stand out in my memory. I think I may have first started keeping a journal after reading ‘1984.’ I knew the author was Russian and thought the novel must be very close to a critique of the early Soviet state and the ideas expressed. Somehow, or no how, I never got around to reading the novel.

A few days ago I decided to listen to the novel ‘Brave New World’ which I have not read. I had an idea that it was supposed to be a future society with totalitarian ‘perfection.’ I had heard of the drug in the book called ‘soma.’

I had recently enjoyed reading a graphic novel of the Iliad and then the Odessey displayed on a big screen while I slowly skated around listening to an audiobook of the story. Some of the graphics are like beautiful watercolors on the crisp screen I have. So, after the couple of nights of listening to a story and seeing the graphic novel I spotted ‘Brave New World’ and paid the $10 to display the work on my screen. I already had an audiobook on my audio account that I had forgotten about. Another work sitting on a virtual shelf.

I swear, as I plunge toward the floor to lie dying I will be thinking of the books I still haven’t read. Serves me right, bloody git, as my mother used to say.

I was curious to see what the author’s take was on the early Bolsheviks and Lenin’s dictatorship or the proletariat. What? The book didn’t seem to be about Leninism. The idea opposed implicitly seems to be ‘futurism.’ Futurists in the pre-WW1 era seemed to be kind of ‘secular’ rationalists who wanted society based on science, not religion, or tradition, or even ‘unpopular’ dogma. Just a kind of sciencism.

As I listen to ‘We’ it seemed like a novel written in the 1960’s, the buildings are all glass and drugs are handed out daily by the beneficent all powerful government. Nothing about Red Guard workers battalions taking over the telephone exchange and evicting the bosses. Not a word about Trotsky’s train moving around the rails to confront the Western Imperialist White Guard troops. I wouldn’t even know the work was Russian. I can’t think of a thing in the work that would stand out to me as Russian or coming from Russian culture.

I also like the voice actor reading the version I have. I recognize the voice from other works and I think he read a lot of the 100 Greatest Books series I have. I do a lot of skating and listening. Lots of books to read before I die.

……………….

I made a graphic for ‘We’ and posted a link to the audiobook on a number of social media platforms.

……………….

I posted links to the audio Mp3 file of the book on Reddit in various subject specific subreddits. I have had some popular posts on r/EuropeanSocialists lately. I did have some posts removed a while ago and stopped putting posts there, but forgot and posted again with success. I think I got a lot of traffic from posting there and the post got upvoted and commented on. But when I checked back a day or so later there was a red ‘X’ and removal banner. Banned again. Reason: liberal Russian emigre opposed to Bolsheviks. Is that true?

The novel does not seem to address the ideas of capitalism versus socialism. The ‘perfect order’ in the glass cities is opposed by revolutionaries in the wild green woods. What puzzles me is did Zamyatin see the inflexible Stalinist perversion of the liberation through socialist organization of work in the early days of the 1917 Revolution and early Soviet state. The novel was published before the Soviet Union was established in 1922. In the midst of the Russian Civil War he saw the seeds of Stalinist totalitarianism? How?

Of course I get the strange pleasure of once again being banned for passing on the work of a writer who was banned. They just won’t stop, will they. But, neither will I, or… “We!”

As previously noted I will be falling to the floor dying at some point in the future, so that will stop me. But, the enemy censors will die, too, at some point.

IWW Song – Should I Ever Be A Soldier (3:25 min) Audio Mp3

NATO’s Napoleon Christmas

The Atheist Handbook to the Old Testament – Joshua Bowen Presentation (1:09:36 min) June 2021

Yevgeny Zamyatin’s We: A dystopian novel for the 21st century – by Michael Brendan Dougherty – 2015

We is a critique of a techno-socialist paradise — and it is more relevant today than ever

JANUARY 10, 2015

The 20th century was haunted by literary visions of a future dystopia. In 1905, Robert Hugh Benson published Lord of the World, in which the Earth is governed by the Antichrist. Later dystopias would be more political: George Orwell’s 1984 (1949) featured a cold, merciless, Party-dominated tyranny, while Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (1932) posited a drugged, manipulated, and productive society. The point of writing a dystopian novel is rather straightforward: for the best authors, it is a way of critiquing current trends and actors by drawing out their ideals and actions to their extreme conclusion.

I’ve loved all of the above, but the dystopian novel most relevant to our time is Yevgeny Zamyatin’s We, which predated Orwell and Huxley, and obviously inspired the former.

Zamyatin wrote We within a few years of the Russian Revolution in 1917. The novel is set 1,000 years after a revolution that brought the One State into power. Citizens are known only by their number, and the story’s protagonist is D-503, an engineer working on a spaceship that aims to bring the glorious principles of the Revolution to space. This world is ruled by the Benefactor, and presided over by the Guardians. They spy on citizens, who all live in apartments made of glass so that they can be perfectly observed. Trust in the system is absolute.

Equality is enforced, to the point of disfiguring the physically beautiful. Beauty — as well as its companion, art — are a kind of heresy in the One State, because “to be original means to distinguish yourself from others. It follows that to be original is to violate the principle of equality.”

While 1984 and other dystopias featured surveillance and telescreens, We is the most analogous to the panoptical surveillance utopia being promoted by the tech gods of Silicon Valley, who seem to admire computers more than they do humans. In We, citizens see themselves as part of a glorious, infallible machine. In the One State, the Guardians and Benefactor urge men to live like machines themselves, so as to avoid even the possibility of failure. “One State Science cannot make a mistake,” Zamyatin writes. He continues:

Why is the dance [of machinery] beautiful? Answer: because it is nonfree movement, because all the fundamental significance of the dance lies precisely in its aesthetic subjection, its ideal unfreedom. [We]

If men show any signs of rebellion, the part of their brain related to passion and creativity is removed through surgery.

Naturally, Zamyatin faced more harassment and punishment for his political views than any of his peers in dystopian literature, and he faced it in both pre- and post-revolutionary Russia. Born in 1884, his early forays into communism drove him into exile, though he returned to Russia during the 1905 Revolution that brought major liberal reforms to tsarist Russia. His involvement in that uprising saw him sent to Spalernaja Prison, where he endured solitary confinement.

Although he would go on to work for the regime’s department of naval architecture, he wrote a fictional work, At the World’s End, that was a satire of life in the military. He was acquitted in a trial over the book’s seditious themes, but all copies of it were destroyed. Although he believed that war and famine could be overcome by collectivism, he soon became distressed at the Soviet Union’s clampdown on the arts. He would later write in a series of samizdat essays, “True literature can only exist when it is created, not by diligent and reliable officials, but by madmen, hermits, heretics, dreamers, rebels, and skeptics.”

………………..

George Orwell Reviews We, the Russian Dystopian Novel – “More Perceptive” Than Brave New World & 1984 – by by Josh Jones (Open Culture) 2017

We know George Orwell’s 1984 and Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, at least by reputation, and we’ve heard both references tossed around with alarming frequency this past year. Before these watershed dystopian novels, published over a decade apart (1949 and 1932, respectively), came an earlier book, one truly “most relevant to our time,” writes Michael Brendan Dougherty: Yevgeny Zamyatin’s We, written in 1923 and set “1,000 years after a revolution that brought the One State into power.” The novel had a significant influence on Orwell’s more famous political dystopia. And we have a good sense of Orwell’s indebtedness to the Russian writer.

Three years before the publication of 1984, Orwell published a review of Zamyatin’s book, having “at last got my hands on a copy… several years after hearing of its existence.” Orwell describes the novel as “one of the literary curiosities of this book-burning age” and spends a good part of his brief commentary comparing We to Huxley’s novel. “[T]he resemblance with Brave New World is striking,” he writes. “But though Zamyatin’s book is less well put together—it has a rather weak and episodic plot which is too complex to summarise—it has a political point which the other lacks.” The earlier Russian novel, writes Orwell, in 1946, “is on the whole more relevant to our own situation.”

Part of what Orwell found convincing in Zamyatin’s “less well put together” book was the fact that underneath the technocratic totalitarian state he depicts, “many of the ancient human instincts are still there” rather than having been eradicated by eugenics and medication. (Although citizens in We are lobotomized, more or less, if they rebel.) “It may well be,” Orwell goes on to say, “that Zamyatin did not intend the Soviet regime to be the special target of his satire.” He did write the book many years before the Stalinist dictatorship that inspired Orwell’s dystopias. “What Zamyatin seems to be aiming at is not any particular country but the implied aims of industrial civilization.”

In the interview at the top of the post (with clumsy subtitles), Noam Chomsky makes some similar observations, and declares We the superior book to both Brave New World and 1984 (which he pronounces “obvious and wooden”). Zamyatin was “more perceptive” than Orwell or Huxley, says Chomsky. He “was talking about the real world…. I think he sensed what a totalitarian system is like,” projecting an overwhelmingly controlling surveillance state in We before such a thing existed in the form it would in Orwell’s time. The novel will remind us of the many dystopian scenarios that have populated fiction and film in the almost 100 years since its publication. As Dougherty concisely summarizes it, in We:

Citizens are known only by their number, and the story’s protagonist is D-503, an engineer working on a spaceship that aims to bring the glorious principles of the Revolution to space. This world is ruled by the Benefactor, and presided over by the Guardians. They spy on citizens, who all live in apartments made of glass so that they can be perfectly observed. Trust in the system is absolute.

Equality is enforced, to the point of disfiguring the physically beautiful. Beauty — as well as its companion, art — are a kind of heresy in the One State, because “to be original means to distinguish yourself from others. It follows that to be original is to violate the principle of equality.”

Zamyatin surely drew from earlier dystopias, as well as the classical utopia of Plato’s Republic. But an even more immediate influence, curiously, was his time spent in England just before the Revolution. Like his main character, Zamyatin began his career as an engineer—a shipbuilder, in fact, the craft he studied at St. Petersburg Polytechnical University. He was sent to Newcastle in 1916, writes Yolanda Delgado, “to supervise the construction of icebreakers for the Russian government. However, by the time the ships actually reached Russia, they belonged to the new authorities—the Bolsheviks…. [I]n an ironic twist, Zamyatin, one of the most outspoken early critics of the Soviet regime, actually designed the first Soviet icebreakers.”

While Zamyatin wrote We in response to the Soviet takeover, his style and sci-fi setting was greatly inspired by his immersion in English culture. His two years abroad “greatly influenced him,” from his dress to his speech, earning him the nickname “the Englishman.” He became so fluent in English that he found work as an “editor and translator of foreign authors such as H.G. Wells, Jack London, and Sheridan.” (During his sojourn in England, writes Orwell, Zamyatin “had written some blistering satires on English life.”) Upon returning to Russia, Zamyatin quickly became one of the “very first dissidents.” We was banned by the Soviet censors in 1921, and that year the author published an essay called “I Fear,” in which he described the struggles of Russian artists under the new regime, writing, “the conditions under which we live are tearing us to pieces.”

Eventually smuggling the manuscript of We to New York, Zamyatin was able to get the novel published in 1923, incurring the wrath of the Soviet authorities. He was “ostracized… demonized in the press, blacklisted from publishing and kicked out of the Union of Soviet Writers.” Zamyatin was unapologetic, writing Stalin to ask that he be allowed to leave the country. Stalin not only granted the request, allowing Zamyatin to settle in Paris, but allowed him back into the Union of Soviet Writers in 1934, an unusual turn of events indeed. Just above, you can see a German film adaptation of We (turn on closed captions to watch it with English subtitles). And you can read Orwell’s full review of We here.

………………..

Related Content:

Huxley to Orwell: My Hellish Vision of the Future is Better Than Yours (1949)

Hear the Very First Adaptation of George Orwell’s 1984 in a Radio Play Starring David Niven (1949)

George Orwell’s 1984 Is Now the #1 Bestselling Book on Amazon

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Looking At – Aldous Huxley’s ‘Brave New World’ – Graphic Novels and Videos

Video Spark Notes – Aldous Huxley – ‘Brave New World’ (10:22 min) https://www.hooktube.com/watch?v=raqVySPrDUE

US: Prolific Radical Liberal doxing account ‘Anonymous Comrade Collective’ revealed (Justice Report) 15 Dec 2022

Ex-journo Hilary Elizabeth Sargent of Roslindale, MA

Disclaimer: The Justice Report utterly denounces the act of “doxing” and recognizes it as a tool widely used by bad actors to intimidate, harass, and divide communities for strictly dishonest purposes. The subject of the following article is so prolific in its doxing of innocent, private people, however, that we feel morally and ethically compelled to report on their identity. Our communities deserve the right to know about the individuals they might share space with.

The identity behind the prolific “Antifa” doxing blog, the Anonymous Comrade Collective, has finally been revealed. Thanks to the combined efforts of Justice Report staff as well as data obtained by a concerned citizen employed in the tech industry, we were able to confirm beyond a reasonable doubt that the user behind the salacious Twitter handle and left-wing extremist blog site is none other than the infamous former Boston Globe journalist, Hilary Elizabeth Sargent, of Roslindale, MA.

(cont. ….. https://archive.vn/nrMfB )