Monthly Archives: April 2022

Black Crime: Why Our Rulers Hide It – by Jared Taylor – 22 April 2022

The absurd excuses the media give for not telling you the perp was black.

https://rumble.com/embed/vzdg8e/ Video Link

This video is available on Rumble, BitChute, and Odysee.

The week began with this headline: “More than 90 shots were fired at a party in Pittsburgh, killing two teens and injuring several others. Here’s what we know.”

What did we know? Besides two dead 17-year-old boys, eight other people were shot but survived. About 200 people were at the party, most of them underage. They were on the second floor, and five people got hurt jumping out the windows. Some broke bones.

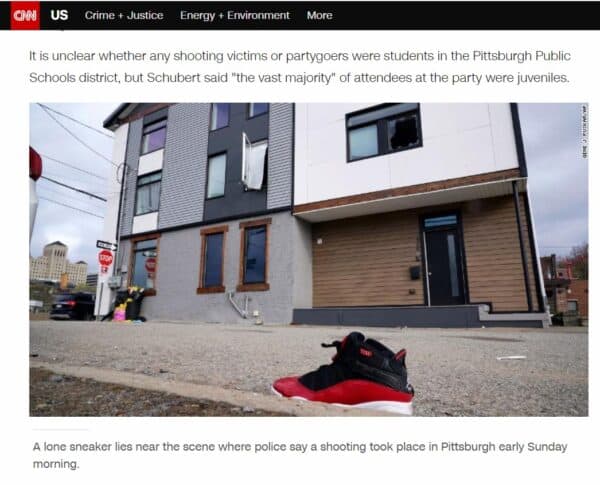

What didn’t we know? Apparently, we had no idea of the race of anyone involved. But there were hints. More than 90 rounds fired and only 10 people hit sounds like a mass shooting by blacks. Also, a photo taken the next day, shows a shoe left behind when a party-goer hot-footed it out of there.

I don’t think many white people wear shoes like that to a party.

Another clue. The party was at an Airbnb rental. It is well known that people who rent Airbnbs, throw huge parties, and wreck the joint are likely to be black.

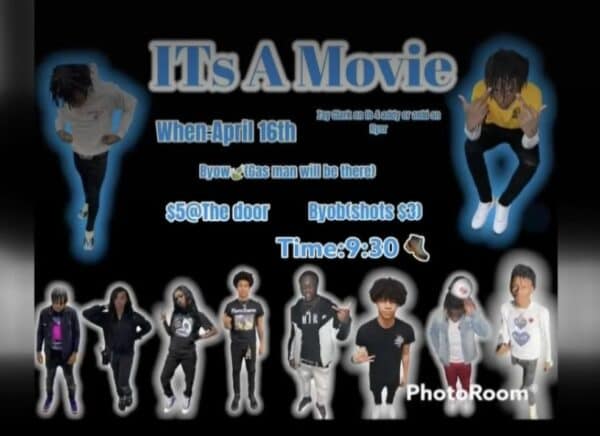

I read just about every article on this shooting — which has already faded from the news — and not one mentioned race. I found an advertisement for the party.

And here is a photo of one of the boys who was killed.

It’s pretty clear that this little drama had an all-black cast, and the suspects — still are large — are black, but the media aren’t telling.

This is an official rule for journalists, as the Cleveland Plain Dealer explained in an article called “The complex issue of identifying suspects by race.”

The author did admit that most people want to the know race of the perp, including, as he noted, a black lady friend whose first reaction to news of a violent crime is, “Please don’t let the person who did it be black.” The author writes that newspapers used to mention race all the time. He cited a 1970 headline, “Policeman Slain Arresting a Negro,” but quickly added, “Nobody I want to be associated with” wants that kind of reporting. But what about the black lady? She wants to know.

Too bad. The Cleveland Plain Dealer follows a rule that is nearly universal: Mention race only if it “is relevant to the news, an integral part of the story, and necessary to the reader’s understanding.”

And so, there was an Airbnb party for 200 people, with guests leaping out of second-floor windows as they were sprayed with nearly 100 rounds, but race is not relevant, not integral, and not necessary to understand the story. We’re supposed to believe that this party could just as easily have been a Young Republicans clam bake or the Wong family reunion. No. Without race, without black people, this story is incomprehensible. Race is the central element; without it, nothing makes sense.

And that’s why the papers leave it out. They don’t want to embarrass the black lady. Or, to use official parlance, to “perpetuate stereotypes.”

Here’s the explanation. “Why the Saint Louis Post-Dispatch doesn’t always identify suspects by race.”

The answer? It can contribute to “stereotypes about one group or another.” I wonder which group. That’s why the Illinois “News-Gazette stopped publishing mugshots through its online portal.”

As it explained, they “can lead to negative stereotypes and discrimination.”

In California, it’s illegal. “New state law prohibits law enforcement from posting mugshots on social media.”

Mugshots might “perpetuate racial stereotypes, overstating the propensity of communities of color to commit crimes.” Mugshots doesn’t overstate anything. They reflect reality. And reality is what our rulers want to hide.

The crowning absurdity is refusing to mention the race of dangerous suspects on the loose. Back to the article in the Cleveland Plain Dealer. It says it has to decide whether including race will really help identify the perp or will only “feed racial fear or hatred.” It says it once got this description from the police: “Two black males, 17-21 years of age, one wearing a gray hooded sweatshirt and black pants, the other wearing all black.” It says that’s not enough to ID the perps. I think it might be all you need. But the paper says mentioning race will just “feed racial fear and hatred,” so it published the description but left race out! Why even publish that? Everyone knows they’re just covering up race.

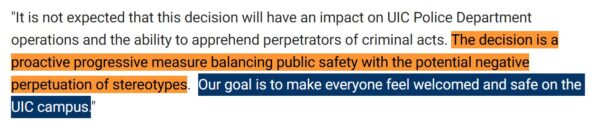

The University of Illinois, Chicago, puts out a safety advisory if there is a criminal on the loose on campus. It’s to warn the students. But last year it announced it would stop mentioning race. As it explained, “The decision is a proactive progressive measure balancing public safety with the potential negative perpetuation of stereotypes.” That means there could be a deranged killer roaming the halls, but we’re not going to tell you he’s black, because we have to balance public safety with perpetuating stereotypes, so to hell with public safety. The notice concluded: “Our goal is to make everyone feel welcomed and safe on the UIC campus.”

Even deranged killers, I guess, so long as they’re black.

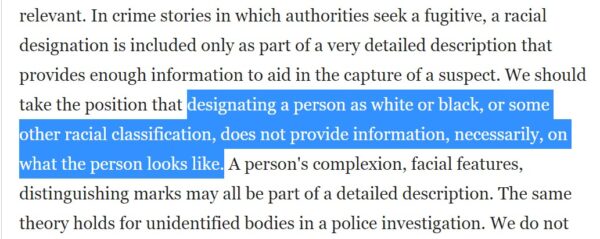

Believe it or not, some people are so determined not to mention race that they insist it doesn’t help identify people. Back to the Post-Dispatch. It says “designating a person as white or black, or some other racial classification, does not provide information, necessarily, on what the person looks like.”

How can they believe that?

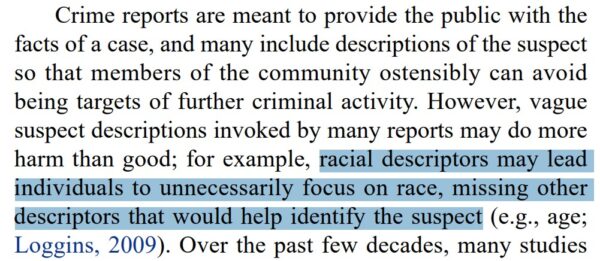

If they do, they are only following the science. Here’s a fancy publication called Personnel Assessment and Decisions. The article is called “The Impact of Suspect Descriptions in University Crime Reports on Racial Bias.”

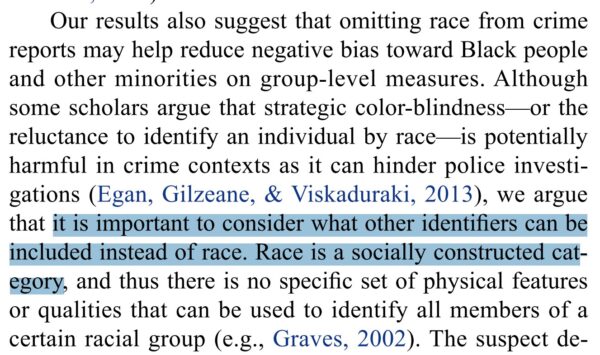

Uh, oh. Racial bias. This article says, “racial descriptors may lead individuals to unnecessarily focus on race, missing other descriptors that would help identify the suspect.”

It adds that “it is important to consider what other identifiers can be included instead of race. Race is a socially constructed category . . . .”

And that is why saying that this guy is black would not help us identify him at all and would just provoke fear and bias.

People spout the craziest stuff to justify not reporting the race of criminals. They just want to hide the truth.

The Washington Free Beacon looked into this. “Yes, the Media Bury the Race of Murderers — If They’re Not White.”

It starts with Frank James, who recently shot 10 people in a subway car in Brooklyn. The article notes that although this guy is an open black supremacist, the New York Times’s 2,000-word article about him said nothing about race. Reuters never mentioned race either.

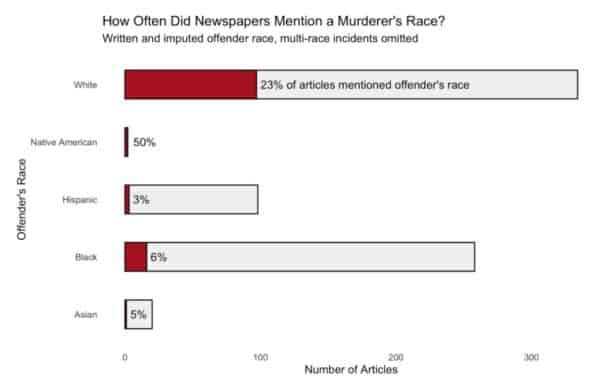

The Free Beacon did a study of 1,100 articles about murder cases from the prestige press between 2019 and 2021. As you can see from this graph, articles mentioned a white murderer’s race 23 percent of the time, a Hispanic’s ethnicity 3 percent of the time, and a black murderer’s race 6 percent of the time.

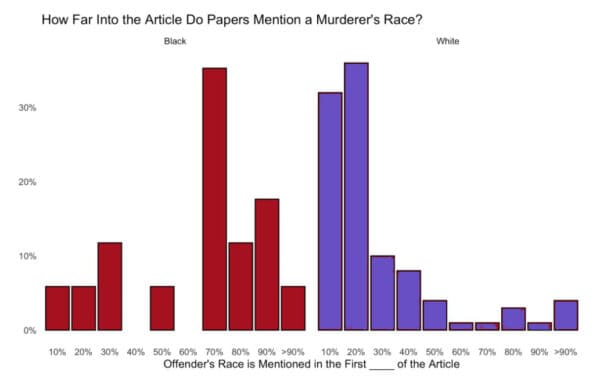

Furthermore, when an article included the race of perp, in half the articles about whites, race came up within the first 15 percent of the article, whereas when a black murder’s race comes it, it is overwhelmingly toward the end.

This graph gives the details.

The red bars show when the article used the word “black.” The most common point was 70 percent into the article, and often even later. Look at the blue lines. The word “white” shows up in the first 10 or 20 percent of the article.

So, the papers mention a white murderer’s race four times more often than a black murderer’s race, and put it in lights early in the article.

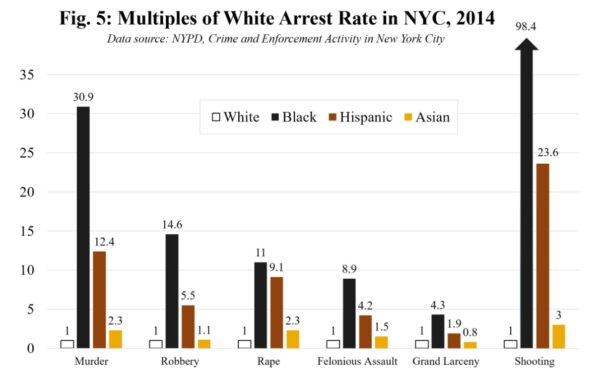

Our rulers clearly don’t want you to know about black crime. They would slit their wrists before they told you that blacks are 13 percent of the population but commit nearly 60 percent of the murders. Or that in New York City, blacks are 30.9 times more likely than whites to be arrested for murder or that, over on the right, they are 98.4 times more likely to be arrested for a shooting offense. You can see that Hispanic crime rates are high, too.

Why do they hide the truth? They would probably say they don’t want to fuel white racism. Facts aren’t racism. Men commit more crime than women. That’s not “sexism,” and no one hides the facts.

But race is different. Race is always different. Our rulers constantly hide the truth — about IQ, crime, mental illness, drug addiction, genetic differences.

Hiding the truth is an essential part of this colossal fraud of pretending that this multi-racial society is going to work and — worst of all — that if it isn’t working it’s *our* fault. We’re supposed to believe that blacks and Guatemalans and Muslims would be just like us if only we would be nice to them.

You can’t build a nation by hiding the truth. You destroy a nation by hiding the truth. And that is exactly what’s happening to the United States.

(Republished from American Renaissance)

Fire Line Drawings – You Spin Me Round Instrumental (3:51 min) Mp3

To The East – Jupiter, Venus, Mars, and Saturn – 4:52am 28 April 2022

Line Drawings – Women – The Video

One Night in Bangkok – Robey – 1985 – (5:10 min) Mp3

Ukraine: Kharkov – Gonzalo Lira Alive – Released by Secret Police After Interrogation (RT) 22 April 2022

Chilean-American blogger Gonzalo Lira, who went missing in the Ukrainian city of Kharkov a week ago, has appeared online on Friday, revealing that he had been held by the Ukrainian Security Service (SBU).

“I’m in Kharkov. I’m OK. I just want to say that I’m back online.” Lira said in short video chat with journalist Alex Christoforou on The Duran channel on YouTube.

“I was picked up by the SBU on Friday, April 15,” the blogger revealed.

Speaking about his condition, the 54-year-old said that he was “fine physically,” but “a little rattled” and “a little bit discombobulated.” Lira made it clear that he was forbidden from revealing any details about what had happened to him in detention.

“I’m still in Kharkov and for the time being I cannot leave. The authorities here told me that I cannot leave the city,” he said, adding that his computer and phone were taken away and that he didn’t have access to his accounts on social media.

“There seems to have been like a lot of interest in my case, which is wonderful. Thank you. But there are a lot of other people, who are frankly more deserving of the attention,” the blogger said.Lira was referring to his tweet from March 26, in which he listed the names of Ukrainian opposition figures, who are thought to have died or disappeared since the outbreak of the conflict, adding then that “if you haven’t heard from me in 12 hours or more, put my name on this list.”

Since the start of the Russian military operation in Ukraine, Lira has been using YouTube, Twitter and Telegram to criticize President Volodymyr Zelensky and Kiev’s conduct on the battlefield, while also speaking about far-right tendencies among the Ukrainian military and debunking what he saw as false reports about events on the ground. After the blogger’s disappearance, some unconfirmed claims emerged that he could have been kidnapped by nationalists linked to the notorious Azov battalion, and even executed.

Lira who penned the novel ‘Acrobat’ and is a filmmaker with Hollywood experience had earlier claimed that the SBU had made at least two other attempts to detain him, but he was lucky to avoid arrest.

Lira also accused the Daily Beast of attracting Kiev’s attention to his work and revealing his location to the country’s law enforcers. The left-wing US outlet dedicated a large article to the blogger on March 21, slamming him as “a Pro-Putin shill in Ukraine.” In the piece, Daily Beast journalists said they had contacted Ukrainian authorities to learn about the man’s whereabouts and to clarify if he was still in Kharkov in the east of the country.

Lira’s week-long disappearance from social media had been largely overlooked by major Western media outlets.

……………………..

Ukraine: Independent Journalist Gonzalo Lira Set Up By Radical Liberal Activist ‘Mark Hay’ of ‘The Daily Beast’ –

Coach ‘Red Pill’ Said to Blame the Daily Beast for His Death

Coach Red Pill AKA Gonzalo Lira said in explicit terms that the Daily Beast would be responsible for his death, as they had written up a hit piece on him and then contacted the Ukrainian security services (SBU) with it and asked them why they haven’t stopped him yet.

Gonzalo Lira has now been missing for a week. He was last heard from on 14 April 2022.

I think it’s safe to say that theories about him getting pinned down and not being able to access the internet are no longer reasonable. There has been some fighting in Kharkov recently, but he’s been in the midst of on-off conflict for months now and has remained online.

Some assume Gonzalo Lira to be captured, and that the moral responsibility lies with the news site called ‘The Daily Beast.’ What people on Twitter calling for ‘The Daily Beast’ to be ‘held responsible’ think is going to happen is a good strange question. The West and the US and EU are lining up for a Cold War and maybe World War Three; the Daily Beast is on the US side hunting down people who are undermining the war effort. For people who support Ukraine against Russia the Daily Beast are the good guys and Gonzalo Lira is a bad guy. Pretty easy to see, unless one lives in a world where moral outrage and logic and fair play rule. Where is that.

Below is a Gonzalo Lira video the Coach did about the Daily Beast report a month ago when it was released.

The piece was allegedly written by someone called Mark Hay, who is some kind of Brooklyn transplant hipster pro-war activist.

‘Mark Hay’ hasn’t tweeted since 2018, and has not written anything since publishing the 20 March 2022 critical article on Gonzalo Lira – despite the fact he’d been covering the “evil white people who support Putin” beat for the Beast in the name of ‘Fighting the Right.’

The kind of journalist who sees Nazis everywhere, except in the openly proud Nazi Azov Battalion which is the backbone of the ‘democratic’ Ukraine army.

Some have studied these hipster activist news journalists that “cover the far right” and don’t understand how they live and make enough money if they are “freelance.” They write a maximum of 2-3 attack pieces a month, which they can’t be getting more than a couple hundred dollars for. I guess most of them live on trust funds, like most hipster anarchists in Brooklyn.

Strange that a ‘journalist’ and activist like ‘Mark Hay’ isn’t on Twitter or Instagram or Gab or other social media. Some checked to see his take on popular topics of the day. “Mark Hay” isn’t on Twitter or any other social media; it would be interesting to see if he feels it is a “mission accomplished” that Gonzalo Lira is now either dead or in some satanic torture dungeon.

Misquotes of Scott Ritter

There are some out of context quotes from Scott Ritter going around that appear to “confirm” the Coach is dead. Scott Ritter says the first quote is a worry about a worst outcome for Gonzalo Lira.

Ritter cleared this up on Twitter, writing that though this is what many people are assuming happened, he doesn’t have any direct evidence this is what happened.

“I don’t know if there is any reason to believe he was killed specifically by Azov. These people do not seem to be very smart, and it would make more sense to sent in the SBU,” wrote one interested blogger.

“Gonzalo Lira should have done like Patrick Lancaster and embedded with the Russians,” the blogger added. “That has its own set of dangers, obviously, and Patrick risks his life every day, but at least if you get killed in that context, it’s not a mystery and you don’t have to worry about being captured and sent to some satanic torture dungeon with Nazis who delight in prolonging pain.”

Angry Crowd Stick Figures

J’ai terminé : 11 livres de Modiano

Patrick Modiano “Dans le café de la jeunesse perdue” – Audio Livre (3:04:06 min)

Patrick Modiano “Pour que tu ne te perdes pas dans le quartier” (Compete) (3:46:08 min) Audio Livre

‘To the Finland Station’ – Edmund Wilson’s adventure with Communism – by Louis Menand – 24 March 2003

The idea for “To the Finland Station” came to Edmund Wilson while he was walking down a street in the East Fifties one day, in the depths of the Great Depression. Wilson was in his late thirties. He had established himself as a critic and reporter with the publication of “Axel’s Castle,” a study of modernist writers, in 1931, and “The American Jitters,” a collection of pieces based on visits he made to mines and factories, in 1932. His ambition, though, was to write a novel. (An early effort, “I Thought of Daisy,” had appeared in 1929; it was not a success.) So he was a little surprised to find himself contemplating an ambitious history of socialist and communist thought, from the French Revolution to the Russian Revolution. But he plainly saw something novelistic in the subject. “I found myself excited by the challenge,” he said later, “and there rang through my head the words of Dedalus at the end of Joyce’s ‘Portrait’ “—“I go to encounter for the millionth time the reality of experience and to forge in the smithy of my soul the uncreated conscience of my race.” He took the title from a novel, Virginia Woolf’s “To the Lighthouse.”

Wilson had been witness to the condition of workers in Appalachia and Detroit—after bringing relief supplies to striking miners in Pineville, Kentucky, he was run out of town by the local authorities—and although he was suspicious of the Communist Party, he welcomed the Crash as a portent of the death of capitalism, and he embraced Marxism. He voted for the Communist candidate, William Z. Foster, in the 1932 presidential election; the same year, he signed a manifesto calling for “a temporary dictatorship of the class-conscious workers.” He was never a Communist, but he did believe that only the Communists were genuinely trying to help the working class. In 1935, after he began work on “To the Finland Station,” he tried to persuade his friend John Dos Passos, whose radicalism had begun to cool, that Stalin was a true Marxist, “working for socialism in Russia.”

Soon afterward, Wilson went to Russia himself. He published his journal of the visit, along with material about travels in the United States, in a book pointedly entitled “Travels in Two Democracies.” In fact, he had had to censor his diaries in order to conceal evidence of the fear and oppression he had seen in the Soviet Union. By 1938, he had stopped pretending. “They haven’t even the beginnings of democratic institutions; but they are actually worse off in that respect than when they started,” he confessed to a friend. “They have totalitarian domination by a political machine.” He understood the implications for the book he was writing. In October, 1939, he sadly informed Louise Bogan, “I am about to try to wind up the Finland Station (now that the Soviets are about to annex Finland).”

“To the Finland Station” was published by Harcourt Brace in September, 1940. It was not the best moment for a book whose hero is Vladimir Lenin. A month earlier, in Mexico, Leon Trotsky had had his head split open with an ice axe. A year before that, the Soviet Union had signed a non-aggression pact with Nazi Germany, effectively allowing Hitler to invade Poland. For five years before that, Stalin had systematically liquidated political opposition within the Soviet Union. The purges were preceded by a program of collectivization that led to the death of more than five million people. By 1940, disillusionment with Communism was well established among intellectuals in the West. André Gide, George Orwell, and Dos Passos had written firsthand accounts of the brutality and hypocrisy of contemporary Communism—Gide and Dos Passos after visits to Russia, Orwell after fighting for the Loyalists in Spain. Partisan Review had already become the organ of the anti-Communist left.

By January, 1947, “To the Finland Station” had sold only 4,527 copies. Doubleday took over the rights and reprinted it that year, but sales continued to be slow. The book did not begin to attract readers until it came out in paperback, as one of the first Anchors, in 1953. It sold decently in the nineteen-sixties, and in 1972, the last year of Wilson’s life, Farrar, Straus & Giroux published a new edition with an introduction by Wilson reassessing his interpretation of Soviet Communism. “This book of mine,” he explains, “assumes throughout that an important step in progress has been made, that a fundamental ‘breakthrough’ had occurred, that nothing in our human history would ever be the same again. I had no premonition that the Soviet Union was to become one of the most hideous tyrannies that the world had ever known, and Stalin the most cruel and unscrupulous of the merciless Russian tsars. This book should therefore be read as a basically reliable account of what the revolutionists thought they were doing in the interests of ‘a better world.’ “

This didn’t entirely meet the difficulty. Wilson did know what was going on in the Soviet Union in the nineteen-thirties, as his pages on Stalin in “To the Finland Station” make clear. The problem wasn’t with Stalin; the problem was with Lenin, the book’s ideal type of the intellectual as man of action. Wilson admitted that he had relied on publications controlled by the Party for his portrait of Lenin. (Critical accounts were available; for example, the English translation of the émigré Mark Landau-Aldanov’s “Lenin” was published, by Dutton, in 1922.) Lenin could create an impression of selfless humanitarianism; he was also a savage and ruthless politician—a “pail of milk of human kindness with a dead rat at the bottom,” as Vladimir Nabokov put it to Wilson in 1940, after reading “To the Finland Station.” In the introduction to the 1972 edition, Wilson provided a look at the rat. He did not go on to explain in that introduction that the most notorious features of Stalin’s regime—the use of terror, the show trials, and the concentration camps—had all been inaugurated by Lenin. “To the Finland Station” begins with Napoleon’s betrayal of the principles of the French Revolution; it should have ended with Lenin’s betrayal of European socialism. Wilson believed that he was writing about the success of ideas in action, about the translation (in the spirit of Stephen Dedalus) of the imagined into the real. But the story he chose was a story of failure.

And yet “To the Finland Station” is, if not a great book, a grand book. It brings a vanished world to life. When you undertake historical research, two truths that sounded banal come to seem profound. The first is that your knowledge of the past—apart from, occasionally, a limited visual record and the odd unreliable survivor—comes entirely from written documents. You are almost completely cut off, by a wall of print, from the life you have set out to represent. You can’t observe historical events; you can’t question historical actors; you can’t even know most of what has not been written about. What has been written about therefore takes on an importance that may be spurious. A few lines in a memoir, a snatch of recorded conversation, a letter fortuitously preserved, an event noted in a diary: all become luminous with significance—even though they are merely the bits that have floated to the surface. The historian clings to them, while, somewhere below, the huge submerged wreck of the past sinks silently out of sight.

The second realization that strikes you is, in a way, the opposite of the first: the more material you dredge up, the more elusive the subject becomes. In the case of a historical figure, there is usually a standard biographical interpretation, constructed around a small number of details: diary entries, letters, anecdotes, passages in the published work that everyone has decided must be autobiographical. Out of these details a profile is constructed, which, in the circular process that characterizes most biographical enterprise, is then used to interpret the details. Yet it is almost always possible to find details that are inconsistent with the standard interpretation, or that seem to point to a different interpretation, or that don’t support any coherent interpretation. Usually, there’s a level of detail below that, and on and on. One instinct you need in doing historical research is knowing when to keep dredging stuff up; another is knowing when to stop.

You stop when you feel that you’ve got it. The test for a successful history is the same as the test for any successful narrative: integrity in motion. It’s not the facts, snapshots of the past, that make a history; it’s the story, the facts run by the eye at the correct speed. Novelists sometimes say that they invent a character, put the character into a situation, and then wait to see what the character will do. The historian’s character has to do what the real person has done, but there is an uncanny way in which this can seem to happen almost spontaneously. The “Marx” that the historian has imagined keeps behaving, in every new set of conditions, like Marx. This gives the description of the conditions a plausibility as well. The person fits the time; the world turns beneath the character’s marching feet. The past reveals itself to have a plot.

This may seem a fanciful account of the way history is written. It is not a fanciful account of the way history is read, though. Readers expect an illusion of continuity, and once the illusion locks in, they credit the historian with having brought the past to life. Nothing else matters as much, and it is hard to see how the reader could have this experience if the historian had not had it first. The intuition of the whole precedes the accumulation of the parts. There is no other way, really, for the mind to work.

This is why historical research is an empirical enterprise and history writing an imaginative one. We read histories for information, but what is it that we want the information for? The answer is a little paradoxical: we want the information in order to acquire the ability to understand the information. At some point, we need the shell of facts to burst, and to feel that we are inside the moment. “Tell me about yourself,” says a stranger at a party. You can recite your résumé, but what you really want to express, and what the stranger (assuming her interest is genuine) really wants to know, is what it is like to be you. You wish (assuming that your interest is genuine) that you could just open up your mind and let her look in. Information alone doesn’t do it. A single intuition of what it was like to be Marx, or Proust, or Gertrude Stein, or the ordinary man on the late-modern street, how they thought and how the world looked to them, is worth a thousand facts, for when we are equipped with the intuition every fact becomes sensible. A residual positivism makes fact and intuition seem to be antithetical terms: hard knowledge versus subjective empathy. This has the priorities backward. Intuitive knowledge—the sense of what life was like when we were not there to experience it—is precisely the knowledge we seek. It is the true positive of historical work.

Wilson had a gift for getting inside the writers he liked (though he had no gift at all for getting inside the writers he didn’t like). Getting inside a historical moment was more difficult. In “Axel’s Castle,” he attempted to create a narrative about modern literature; in “Patriotic Gore,” he attempted to create one about the United States during the Civil War and its aftermath. Neither book successfully transcends its parts. This was because Wilson had a journalist’s queasiness about big ideas. Abstraction is the reporter’s natural enemy, and Wilson favored nice, low-concept metaphors: the pendulum theory of literary history, in “Axel’s Castle” (realism swings to symbolism, and back); the wound theory of artistic creation, in “The Wound and the Bow” (art as compensation for psychic pain); the sea-slug theory of history, in “Patriotic Gore” (the Civil War as a case of the universal tendency of the larger entity to consume the smaller). These are premises that kill contexts; they reduce everything to a single-term explanation. Wilson could get inside Proust and Joyce, in “Axel’s Castle,” and inside Abraham Lincoln and Oliver Wendell Holmes, in “Patriotic Gore”; but those books read more like a series of portraits than like a narrative.

“To the Finland Station” is different. The structure is simple: the decline of the bourgeois revolutionary tradition after the French Revolution, as Wilson sees it reflected in the writings of Jules Michelet, Ernest Renan, Hippolyte Taine, and Anatole France; the emergence of revolutionary socialism, seen through the writings of Saint-Simon, the communitarians Charles Fourier and Robert Owen, and Marx and Engels; the triumph of Communism, illustrated by the careers of Lenin and Trotsky. There are things Wilson minimized that would have complicated this narrative: the persistence of a non-Communist socialist ideal in Western Europe; the liberal tradition in Russian politics (to which Nabokov’s father belonged); the success and failure of the Mensheviks, of whom Wilson did not make much. And, of course, if the book were being written now, the vicious side of Marxist and Leninist thought, mostly a subtext in Wilson’s account, would guide the narrative, and the story would touch down in Siberia or Berlin rather than at the Finland Station.

But we don’t read “To the Finland Station” as a book about the Russian Revolution anymore. What draws us now is the subtitle: “A Study in the Writing and Acting of History.” History is the true subject of Wilson’s book, and what he evokes is what it felt like to believe—as Vico and Michelet, Fourier and Saint-Simon, Hegel and Marx, Lenin and Trotsky all believed—that history holds the key to the meaning of life. The evocation is successful because when Wilson began writing “To the Finland Station” he believed in history, too. He thought that history had a design, and that the Depression was an event fully comprehensible within the context of that design: it was the long-predicted collapse of the capitalist order. “To the Finland Station” is valuable as a window on the nineteenth century, but it is also a poignant artifact of the nineteen-thirties, a time when many people thought that history was something you could get on the right side or the wrong side of. It was an idea indistinguishable from faith, and Marx was one of its prophets.

Marx was a man of the eighteen-forties—like Dostoyevsky, Herzen, Bakunin, Baudelaire, Flaubert, Wagner, and Mazzini. All of them were shaped by the promise and the collapse of the European revolutions of 1848. They had dreamed that the world was about to turn a corner, a corner it had tried to turn once before, at the time of the French Revolution, and that nothing would ever be the same; and when they awoke the old order was still there—in many ways more reactionary and more philistine than ever. This is the story that Flaubert told in “Sentimental Education,” and it is what Marx was referring to in the famous phrase in “The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte”: “the first time as tragedy, the second as farce.”

In the decades that followed the failure of the 1848 revolutions, the North Atlantic states underwent an industrial and technological growth spurt that completed the process of modernization and established capitalism as a complete social and economic system. Capital became the great solvent in everyday life; change was the new constant. This was the world of which Marx aspired to be the champion analyst. “Uninterrupted disturbance of all social conditions, everlasting uncertainty and agitation” was the way he described it. The words were written on the eve of the 1848 revolutions. They are, of course, from “The Communist Manifesto”: “All fixed, fast-frozen relations, with their train of ancient and venerable prejudices and opinions are swept away, all new-formed ones become antiquated before they can ossify. All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned, and man is at last compelled to face with sober senses, his real conditions of life, and his relations with his kind.”

Marxism was a consolation for this condition. It said that, wittingly or not, the individual performs a role in a drama that has a shape and a goal, a trajectory, and that modernity will turn out to be just one of the acts in that drama. Change is not arbitrary. It is produced by class conflict; it is faithful to an inner logic; it points toward an end, which is the establishment of the classless society. Marxism was founded on an appeal for social justice, but there were many forms that such an appeal might have taken. Its deeper attraction was the discovery of a meaning, in which human beings might participate, in history itself.

The thinker standing behind the Marxian idea of history was Hegel, and Hegel gave Wilson the most trouble in writing his book. “My great handicap, I find, in dealing with all this is my lack of grounding in German philosophy,” he confessed to his old Princeton teacher Christian Gauss in 1937. “Dialectical materialism, which was in revolt against the German idealistic tradition, really comes right out of it; and you would have to know everybody from Kant down to give a really sound account of it. I have never done anything with German philosophy, and can’t bear it, and am having a hard time now propping that part of my story up.” He never did get it figured out.

The dialectic was just the sort of high-theory concept that Wilson reflexively avoided. At the same time, he was not a man quick to concede his ignorance, and he devoted a chapter of his book to explaining that the dialectic is basically a religious myth (a characteristic exercise in journalistic debunking). Wilson had no idea what he was talking about. The two-paragraph explanation he gives of the term at the beginning of the chapter on “The Myth of the Dialectic”—the thesis-antithesis-synthesis model—is not the dialectic of Hegel. It is the dialectic of Fichte. And Marx and Engels did not name their method “dialectical materialism.” That was a term assigned to it by Georgi Plekhanov, the man who, after Marx’s death, introduced Marxism to Russia. Engels referred to the method as historical materialism.

Still, Hegel’s dialectic was part of Marx’s way of doing philosophy, and the use of the dialectic as a historical method is the strongest element in Marxist theory. In the broadest terms, it is a way of treating each aspect of a historical moment—its art, its industry, its politics—as being implicated in the whole, and of understanding that every dominant idea depends on, defines itself against, whatever it suppresses or excludes. Dialectical thinking is a brake on the tendency to assume that things will continue to be the way they are, only more so, because it reminds us that every paradigm contains the seed of its own undoing, the limit-case that, as it is approached, begins to unravel the whole construct. You don’t have to be an enemy of bourgeois capitalism, or believe in an iron law of history, to think this way. It’s just a fruitful method for historical criticism.

Wilson was not drawn to dialectical thinking—he mocks “the Dialectic” in nearly all his writings on Marxism—in part because thinking dialectically is something that American intellectuals don’t naturally do. John Dewey was one of the few who did, and Dewey was trained as a Hegelian. American critics tend to prefer a binary analysis: thumbs up or thumbs down, right or left, tonic or toxin. It is difficult for them to see that most cultural products work in several ways at once. It is even harder for them to see that each element in a cultural system depends for its value on all the others—so that to alter one element is to alter every element. Their overpowering impulse is, like Wilson’s, to isolate and to simplify. “To the Finland Station” stands out from the rest of Wilson’s work because it succeeds in representing history as a reciprocal interaction between individual agency and social force. And, whatever Wilson’s hopes and intentions, it does expose in Marxism the seeds of its own undoing.

What is most characteristic in American criticism is something that Wilson had plenty of. He was a literalist and a skeptic. He believed, when he started his book, that Marx and Engels were the philosophes of a second Enlightenment. The notion appealed to him because he himself was, in many respects, a man of the eighteenth century (and liked to say so in later life). The pose of seeing through other people’s fancy phrases was part of this persona. Empiricism and common sense—Hume and Johnson, the reporter and the critic—were all the philosophy that Wilson required. What he most admired about Marxism was the practical side: people were suffering under the conditions of industrial capitalism, and something needed to be done for them. He thought of the theory as simply an interesting example of the use of ideas as a spur to action.

By the time Wilson came to the end of his book, though, he had become wary of the idealization of history that he saw as endemic to Marxism. He describes this as the notion that history “is a being with a definite point of view in any given period. It has a morality which admits of no appeal. . . . Knowing this—knowing, that is, that we are right—we may allow ourselves to exaggerate and simplify.” After describing Trotsky’s speech to the Mensheviks following the Bolshevik seizure of power—“You are pitiful isolated individuals. . . . You are bankrupt; your role is played out. Go where you belong from now on, the rubbish-can of history!”—Wilson observes, mildly:

There sometimes turn out to be valuable objects cast away in the rubbish-can of history—things that have to be retrieved later on. From the point of view of the Stalinist Soviet Union, that is where Trotsky himself is today; and he might well discard his earlier assumption that an isolated individual needs must be “pitiful” for the conviction of Dr. Stockman in Ibsen’s Enemy of the People that “the strongest man is he who stands most alone.”

This grim independence was something Wilson admired in Marx, and something he might have wished to feel true, with some justice, of himself.

The more one thinks about Wilson’s headstrong character and his antipathy to systematic thought, the more remarkable his devotion of so many years of his life to this book—which required him to learn both German and Russian. Possibly it can be explained by saying that, in the end, Wilson was a writer, and he thought he had found a good story. The stubbornness and independence also help to explain why, unlike most American intellectuals of his generation, Wilson did not rebel against the politics of his youth. He renounced Communism and the Soviet Union, but he did not become an anti-Communist crusader. One of his later books, “The Cold War and the Income Tax,” was an attack on anti-Communism and American foreign policy, and a book so intemperate that it was received as virtually anti-American. Around the same time Wilson published it, he set out to create an “American Pléiade”—the project that has now been realized as the Library of America. He chose to be a patriot on his own terms.

Among other surprising things, “The Cold War and the Income Tax” disclosed how little money Wilson had made from his writing. His sense of vocation was too urgent for him to calculate the impression he might be creating. In the last decades of his life, he shuttled between Wellfleet, on Cape Cod, and Talcottville, in upstate New York, indifferent to almost everything but his story of the moment: Russian writers, the literature of the Civil War, the Dead Sea Scrolls. He resembled the great isolatoes he had brought to life in the pages of “To the Finland Station,” Michelet, Babeuf, Saint-Simon—above all, Marx himself, writing ceaselessly, his books selling few copies, his wife ill, his children crawling all over him, the rent collector at the door, and his inner gaze fixed raptly on history, the courtesan of every ideology. ♦

Crime Causes Poverty – by Stanton E. Samenow Ph.D. (Psychology Today) 24 Dec 2014

“The truth is that criminologists don’t know exactly what the economy’s impact on crime really is. While the U.S economy prospered in the 1960s, the nation’s homicide rate rose 43 percent. Yet, in the mid-1990s when the U.S economy was again prospering, the nation’s crime rate began to fall. Most recently during the great recession of 2008-09, the crime rate did not rise, but remained stable. […] given all the discussion among politicians and media pundits about the relationship between the economy and crime, it’s interesting to see that the rhetoric isn’t based on much evidence.” (Min fetmarkering)

“[I]t may come as a surprise that the scholars who have looked most closely at the presumed connection between crime and employment disagree as to what that connection is, or even whether it exists at all.”[2]

“While research findings generally suggest that social disadvantage (typically in reference to families and neighborhoods) is somehow implicated in crime causation, there is far from a simple one-to-one relationship, and researchers avidly disagree about the strength and nature of this relationship, with some even questioning whether there is a relationship at all” (Min fetmarkering).[3]

“When I was a young professor — when I was studying these matters — it was always told to us that there is this huge relationship between poverty and crime, between economics and crime. And I sort of accepted this like everybody else. When I did this book, I learned that the issue is more complicated than we thought. First off, as I said earlier, general economic conditions and violent crime are not consistently related.” (min fetmarkering) [5]

“Sutherland [a sociologist and highly influential criminologist] is quoted from his earlier writings as observing that while crime is strongly correlated with geographic concentrations of poor persons, it is weakly correlated (if at all) with the economic cycle. That is, crime may be observed to increase as one enters a poor neighborhood, but it is not observed to increase as neighborhoods generally experience a depression, or to decrease as they experience prosperity. “Poverty as such,” Sutherland concludes, “is not an important cause of crime.”” (min fetmarkering) [6]

“When Charles R. Tittle, Wayne J. Villemez, and Douglas A. Smith reviewed thirty-five studies of the relationship between crime rates and social class, they found only a slight association between the two variables.“ [7]

“I do not say this to explain away the studies purporting to show that unemployment or poverty causes crime, for in fact (contrary to what many people assert) there are very few decent pieces of research that in fact show a relationship between economic factors and crime. Robert W. Gillespie reviewed studies available as of 1975 and was able to find three that asserted the existence of a significant relationship between unemployment and crime but seven which did not. Thomas Orsagh and Ann Dryden Witte in 1981 reviewed the studies that had appeared since 1975 and found very little statistically strong or consistent evidence to support the existence of a connection. The evidence linking income (or poverty) and crime is similarly inconclusive, and probably for the same reasons: there are grave methodological problems confronting anyone trying to find the relationship […] To quote Orsagh and Witte: “Research using aggregate data provides only weak support for the simple proposition that unemployment causes crime . . . [and] does not provide convincing tests of the relationship between low income and crime.” [8]

“A popular theory of crime is that it is due to poverty and unemployment. However, crime in the UK increased sharply between 1950 and 1970 when we “never had it so good” and is now falling, despite “austerity”. Crime in the US also fell recently through a period of rising unemployment. The links between unemployment levels and crime are often surprising. During the time Hugo Chavez controlled Venezuela (1999-2013) unemployment was roughly halved but the murder rate tripled (Sedghi, 2013). “[9]

“As Glaeser observed, cities in very similar circumstances in terms of key socioeconomic variables often have widely differing crime rates. […] long-term history of crime teaches us that economic downturns and upswings are inconsistently related to violent crime” [10]

“The bottom line is that criminologists haven’t been able to draw any definitive conclusions about income as a crime-causing factor”[11]

“Thomas Orsagh and Ann Dryden Witte reviewed the studies that appeared between 1975 and 1981 and concluded that they supplied very little strong, consistent support for the claim that unemployment and crime are connected. In their words, “Research using aggregated data [i.e., data pertaining to geographic areas, such as cities or states] provides only weak support for the simple proposition that unemployment causes crime. When the Vera Institute in New York City undertook its own evaluation of the literature, the strongest statement it could make was that “studies based on aggregate statistics present mixed results” and that “social experiments have not fully demonstrated the impact of employment programs on crime. […]Freeman went over this now well-plowed terrain one more time and, though clearly sympathetic to the view that crime and unemployment were related, concluded by saying that this relationship is “not an open-and-shut case“[…]We have already noted earlier in this chapter that the results of many of these efforts [to measure a connection between unemployment and crime] were inconclusive. This is especially true of the cross-sectional studies that compare cities, metropolitan areas, or states. Freeman considered fifteen of these and found only four that showed a clear (statistically significant) relationship in the predicted direction (i.e, that higher unemployment is associated with more crime).” [12]

“Some people hate the welfare state, and have a tendency to blame it for crime. Others like the welfare state, attributing crime to not having more of it. I maintain that crime variation in industrial nations have nothing to do with the welfare state. In general, it is a mistake to assume that crime is part of a larger set of social evils, such as unemployment, poverty, social injustice, or human suffering. I call this the Welfare-state fallacy.

It is interesting to see partisans on this issue pick out their favorite indicators, samples of nations, and periods of history in trying to substantiate their assertions. We see all the economic indicators rising with crime from 1963 to 1975 […] We see the same indicators changing inversely to crime in the last few years in the United States. We also note that most crime rates went down during the Great Depression.

I first realized that the welfare crime linkage was mistaken when studied crime rate change since World War II. Improved welfare and economic changes, especially for the 1960s and 1970s, correlated with more crime! I next recognized something was wrong with the hypothesis when I learned that Sweden’s crime rates increased 5-fold and robberies 20-fold during the very years (1950 to 1980) when its Social Democratic government was implementing more and more programs to enhance equality and protect the poor […] Other “welfare states” in Europe (such as the Netherlands) experienced at least as vast an increase in crime as the United States, whose poverty is more evident and social welfare policies are stingier. […]

This is not an argument against fighting poverty or unemployment. Rather, it is an attempt to detach criminology from a knee-jerk link to other social injustice, inequality, government social policy, welfare systems, poverty, unemployment, and the like. To the extent that crime rates respond at all to these phenomena, they may actually increase with prosperity because there is more to steal. In any case, crime does not simply flow from other ills.” [15]

“No consistent relationship between the extent of a group’s socioeconomic disadvantage and its level of violence is evident. Impoverished Jewish, Polish, and German immigrants [to America] had relatively low crime rates, while disadvantaged Italian, Mexican, and Irish entrants committed violent crime at very high rates. This crime/adversity mismatch is evident in other countries as well and is probably a global phenomenon. In an analysis of ethnicity and crime in contemporary Great Britain, for instance, David J. Smith candidly observed that ‘all of the minority groups with elevated rates of crime or incarceration are socially and economically disadvantaged, but some disadvantaged ethnic minority groups do not have elevated rates of offending.’ He noted that the homicide suspect rate in the United Kingdom was 5.4 times as high for Afro-Caribbeans and Black Africans as for the general population, but it was only 2.2 times higher for Asians. This was surprising because Smith thought that blacks were less disadvantaged than Asians educationally, or in material well-being. They lived in less racially segregated neighborhoods, and their experience with discrimination at the hands of the justice system and the general public seemed to be no worse than that of Asians. […]

The Haitians [that immigrated to the United States during the 80s] illustrates another point: culture trumps adversity, for both immigrants and natives, but most noticeably for immigrants. It would be hard to match Miami Haitians for hard knocks. Black, poor, uneducated, and unwelcome, they somehow managed to avoid assaulting their neighbors. Was this due to their religiosity? The strength of their families? Until scholars address these questions one must conclude only that something about Haitians – call it Haitian culture – enabled them to transcend economic and social disadvantage and conform to American Law. […]

These émigrés, wrote Alejandro Portes and Alex Stepick, ‘compare poorly with American Blacks or Mariel Cubans’. On average, none had advanced beyond fifth or sixth grade, and about four-fifths spoke little or no English. In Haiti, about a third had been jobless (unemployed or not looking for work) before they decided to leave. Once in the United States, nearly six in ten were below the poverty line, and virtually all of these immigrants were black and subjected to the same levels of discrimination experienced by African Americans. […] Despite all of their adversities, Haitians had rather low crime rates. Martinez and Lee’s 1985-95 study reported a homicide victimization rate of 16.7 for Haitians [the murder rate for different ethnic groups is often assessed by looking at the of homicide victimization rate – due to very few murders being interethnic], which was lower than those for non-Hispanic whites and Latinos and far lower than the rate for American blacks. In fact, the Haitian crime figures may be inflated” (min fetmarkering) [16]

“The idea that crime results from poverty may stem from the observation that all social problems tend to congregate within the same inner-city areas. In this sense, bad housing and education, unemployment, drugs and crime rates all go together […] However, it is simple-minded to attribute one social problem to another. People in these areas also elect Labour councils, yet not so many sociologists ascribe crime to voting Labour. Correlations do not confirm cause and effect.” [18]

“some people may turn to crime because they are poor, some people may be poor because they have turned to crime but are not very good at it, and still other persons may have been made both poor and criminal because of some common underlying factor” [19]

“40 to 50 percent of the variability among us in antisocial behavior is explained by genetics. […]Half of the answer to why some of us are antisocial while others are not is due to genetics. […]We must be very cautious not to overestimate the importance of genetic factors, but all in all there is no question that antisocial behavior is heritable—and significantly so” [22]

“Study after study has shown that a willingness to commit antisocial acts, including lying, stealing, starting fights, and destroying property, is partly heritable (though like all heritable traits it is exercised more in some environments than in others)” [23]

“Rather than inequality causing criminality, criminality can contribute significantly to increasing inequality. When a person is incarcerated, his family’s resources, however limited, become even more strained. The standard of living drops when a regular paycheck ceases. A small business victimized by a criminal may be forced to close, impoverishing the owner and employees.” “What may not be apparent is that crime causes poverty.” [27]

“Any broad-brush discussion of cultural patterns must, of course, not claim that all people – whether white or black – had the same culture, much less to the same degree. There are not only changes over time, there are cross-currents at a given time. Nevertheless, it is useful to see the outlines of a general pattern, even when that pattern erodes over time and at varying rates among different subgroups”[31]

…………………

Morning Has Broken – Medieval Style – Bardcore (2:01 min)

Is Picasso Being Cancelled? (AFP) 6 April 2022

2 min

Paris (AFP) – Pablo Picasso’s track-record with women certainly would not make him a feminist pin-up today.

There were two wives, at least six mistresses and countless lovers — with a tendency to abandon women when they became ill, a voracious appetite for prostitutes, and some eye-popping age differences (his second wife was 27 when he married her at 79).

Some of the quotes attributed to him would probably cause Twitter’s servers to combust if he said them now (“For me there are only two kinds of women: goddesses and doormats”).

None of this is new — it has been recycled through books and articles from (sometimes traumatised) family members since soon after his death in 1973.

But in a post-MeToo world, it poses a challenge for those who manage his legacy.

“Obviously MeToo tarnished the artist,” said Cecile Debray, director of the Picasso Museum in Paris.

But she added: “The attacks are undoubtedly all the more violent because Picasso is the most famous and popular figure in modern art — an idol that must be destroyed.”

‘Perverse, destructive’

Not that the issue is being brushed under the carpet.

The Paris museum has recently invited women artists to respond to the debate, including “Weeping Women Are Angry” by French painter Orlan (a reference to one of his most famous portraits, “The Weeping Woman”).

The sister museum in Barcelona is holding workshops and talks this May with art historians and sociologists to unpack the issue.

The experts are, however, critical of some recent hit-jobs on their beloved master.

An award-winning French podcast on the topic has reignited the debate, leaning heavily on a 2017 book by journalist Sophie Chauveau, “Picasso, the Minotaur”, for whom the artist was “violent… jealous… perverse… destructive”.

Debray said some of their claims were “anachronistic” and given to “conjecture and assertions without historical references”.

But she still welcomed the challenge, saying: “The history of art is nourished by the questions of our time and new generations.”

‘Animal sexuality’

Nor is it simple to separate the artist from the art.

Of her grandfather’s women, Marina Picasso once wrote: “He submitted them to his animal sexuality, tamed them, bewitched them, ingested them, and crushed them onto his canvas.”

But, says another grandchild Olivier Picasso, depicting Picasso as a monster risks removing the agency of the women who loved him.

Some, like Marie-Therese Walter, were young and vulnerable muses who felt discarded (she later killed herself), he told AFP.

But others, like Francoise Gilot, knew exactly what they were getting with Picasso and had no problem walking away when they had had enough.

“Some came out of it well, but for others it went badly,” he said. “It’s all very complicated — these women don’t resemble each other.”

The paintings themselves show some of that complexity.

“There are violent works, others that are very tender, very soft… Each time, after exhausting his inspiration, he moves on to something else,” he said.

“Women were necessary to his creations and without them, there would have been something missing.”

……………………………..