Even in the surreal, insular world of leftist propaganda papers, the Spartacist League’s Workers Vanguard is a standout.

15 April 1993

…………………..

Rush Limbaugh makes a good living denouncing the allegedly immense power of the left in American life. It would be comforting for me, as a confirmed pinko ideologue, to believe Limbaugh’s fantasy of leftist omnipotence. But alas, most leftist organizations in this country would have a hard time organizing a good picnic, much less the Revolution.

The American left is marginalized in so many ways that it is more than a little discouraging to see how often, and how thoroughly, it marginalizes itself. A great many of those whose political sympathies are close to mine have retreated from politics to the comfort, such as it is, of the academy, seeming to believe that deconstructing a text is equivalent to mounting a barricade, and taking a certain pleasure in elaborating an incomprehensible postmodern nihilism. There are worse hobbies, I suppose, than French critical theory, though I wish the academic hobbyists wouldn’t be so insistent about regarding what they’re doing as politics.

It’s easy enough to criticize the academic left. But what distresses me more is the marginality of the organized left, which is as divorced from the politics of the real world as its academic counterpart. In many ways the current situation is a response to the failures of the 60s: the academics have responded to failure, in practical terms, by giving up any hope of influencing the world beyond the campus; the organized leftists in too many cases by circling the ideological wagons, holding ever more tightly to the dogmas that got them into this mess in the first place.

American Marxists have always lacked the imagination of their international counterparts. “For the pragmatical American mind,” radical critic Edmund Wilson once noted, “the ideas and literature of Marxism are peculiarly difficult to grapple with; and the American, when converted, tends to accept them, as he does Methodism or Christian Science, as a simple divine revelation.” This was true in the Popular Front 1930s (Wilson was writing in 1941), when most radical thinkers swallowed without question the debased Marxism of Stalin; it was true in the 1960s, when radicals in SDS turned to delusional varieties of Maoism to provide them with theoretical rigor on the cheap; and it’s true today.

With little influence in the wider world, most left groups these days concentrate on “propaganda” work–they still use the old term–among their vaguely sympathetic peripheries. These groups–most with membership rolls in the low hundreds, if that–go to enormous effort to produce and distribute newspapers (usually once or twice a month), many of which (given the extraordinarily meager resources of their sponsors) are surprisingly thick and surprisingly slick.

Some of the smaller sects have little more than a newspaper to attest to their existence, and these papers may have circulation lists not much longer than their mastheads. Among the most radical groups, though, newspapers are pretty much de rigueur; Lenin had one, you see, and so every aspiring Leninist group, no matter how small, feels obligated to put out its own version of the truth. The titles of the papers ring changes on an old tune: Socialist Worker, Revolutionary Worker, Fighting Worker, Workers Vanguard, Workers Truth, Workers World. (As Dwight Macdonald once observed, originality in nomenclature is not one of the American left’s strengths.)

The tone of the papers alternates between a kind of utilitarian dreariness–as the writers attempt to adapt the facts of the world to fit whatever dogmas the group espouses–and the extravagant rhetorical posturing that comes so easily to those who believe they have history on their side. None of this is exactly new: looking back on his experience with the communist movement in the 1930s, poet Stephen Spender came to the sad conclusion that “nearly all human beings have an extremely intermittent grasp of reality.” The Communists he knew saw just what they wanted to see, filtering the world through the lens of Marxian teleology–convinced, as Spender put it, “that their ‘line’ is completely identifiable with the welfare of humanity and the course of history, so that everyone outside it exists only to be refuted or absorbed into the line.” It takes a certain chutzpah to believe that your tiny group holds the future in its hands, but Marxian dogma (like most dogma) can be heady stuff.

The papers are a varied lot. Some are so extravagantly strange that they appear almost to have dropped in from another dimension. The highly secretive, pretentiously named Maoist International Movement (MIM), invisible here in Chicago as an organization, manages to distribute its newspaper, MIM Notes, to certain cafes and bookstores in the area. The writing itself is fairly rabid–the group believes American workers have been bought off by the rewards of capitalism and denounces them with the fury most groups reserve for the capitalists themselves. More disconcerting, the writers themselves go by code names, odd combinations of letters and numbers; the masthead of MIM Notes seems almost to be written in hieroglyphs.

Less rabid, but no less surrealistic, is the small monthly bulletin News and Letters, put out by a group of new-age Marxist-Humanists dedicated to spreading the word of the late Raya Dunayevskaya, an obscure Trotskyist Madame Blavatsky. Her writings are a mixture of dialectics and Marxian mysticism. Here’s a typical passage: “I’m going to make ‘pure’ abstraction of the Self-Thinking Idea, a veritable Universal, because I wanted, first of all, to firmly establish that the Self-Thinking Idea does not–I repeat, does not–mean you thinking.” Her followers–seen selling the paper at most Chicago-area demonstrations–are invariably soft-spoken, reassuringly modest.

The more visible Revolutionary Communist Party (“Mao more than ever!”) recruits among anarchists and cultural radicals, and the leaders do their best to keep up with the youngsters. But they try a little too hard, and the RCP paper Revolutionary Worker often comes across as a parody–the language a mixture of Maoist dogma, 1960s-era countercultural slang, and an imaginary dialect that the editors must suppose to be the language of today’s youth. The editors don’t ask their readers to join them in the Revolution–they call for us to “get down for the whole thing.” (During a subscription drive, they asked readers to “get down with the drive to subscribe.” ) In the midst of the past election season the paper offered “straight talk on the voting thang.” More advanced young revolutionaries can read Chairman Bob Avakian’s “Democracy: More Than Ever We Can and Must Do Better Than That.”

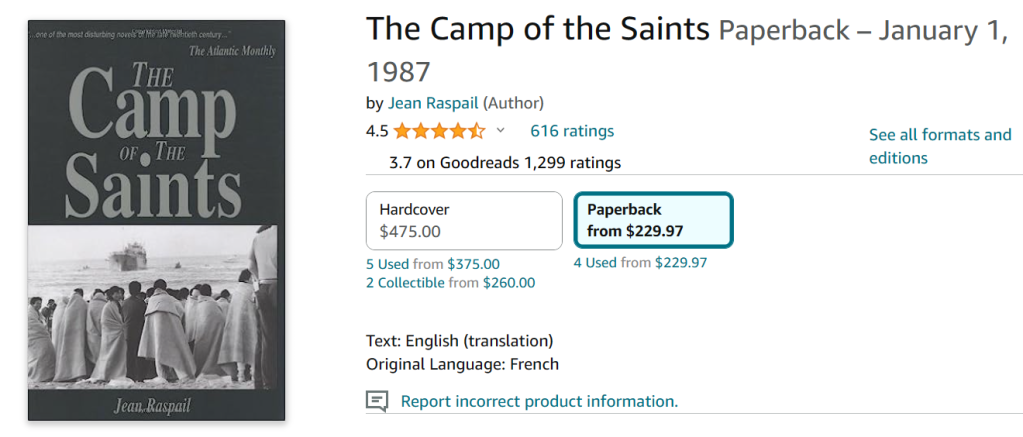

The most revealing sectarian paper, though, and my own personal favorite, is Workers Vanguard, the biweekly production of a little group called the Spartacist League, one of the odder emanations of the American Trotskyist tradition. (Yes, Virginia, there are still Trotskyists.) Leon Trotsky’s legacy has been a decidedly mixed one. He was a brilliant theoretician and an often magnificent writer–but he was also pigheaded, and he left behind almost as many bad ideas for his followers to chew upon as good ones. The Spartacists, like all of the more orthodox Trotskyists, have picked up many of the old man’s bad ideas and much of his pigheadedness.

The Spartacist League emerged in 1966, fully formed, from the Socialist Workers Party, then the largest American Trotskyist group. The American Trotskyist movement, from which both of these groups emerged, has had what might charitably be called a checkered history. At its height in the 1930s, the American Trotskyist movement captured the allegiance of many of the country’s most important left intellectuals and helped to lead militant strikes to victory, most notably in Minneapolis; alone on the left they stood up to the lies and evasions of Stalin and his American supporters. But American Trotskyism has been particularly prone to sectarian infighting and has proved incapable of reaching a mass audience. The movement has always been a magnet for cranks–of which the Sparts, as they are affectionately known, are merely the most extravagant example.

Workers Vanguard, like the Spartacist League itself, tries hard to project an image of high seriousness–none of the RCP-style hankering after hipness. The paper is distinguished both by the ferocity of its language and the intemperance of its ideological content. Much of the paper consists of virulent attacks on other leftist groups; among hard-core aficionados of leftist gossip the WV serves almost as a kind of sectarian National Enquirer, detailing in vivid language the squabbles between the Sparts and the rest of the left. (As a public service of sorts, the Sparts also reprint attacks on them by their critics, which appear in a special series called “Hate Trotskyism, Hate the Spartacist League.”)

Spart attacks often devolve into interminable diatribes, written in the arcane shorthand of Leninist sectariana. Toward the end of a 5,000-word article entitled “Collapse of Stalinism Shakes Pseudo-Trotskyists: The New Anti-Spartacists,” we find this choice example of Spartspeak: “But swimming against the stream is anathema to the Pabloites, whose liquidationist revisionism destroyed the Fourth International . . . abandoning the struggle for a Trotskyist proletarian vanguard in favor of tailing after ‘substitutes’ led by alien class forces.” Even getting through the headlines requires a Marxist glossary: where else could you find articles titled “CPUSA Comes out for Social-Fascist Bloc” and “S.F. Cop Bonapartism and the Gay Paper Caper”?

At times, the Spart diatribes achieve a kind of poetry. My favorite leaflet concerns an alleged brawl between the Canadian equivalents of the Sparts and another Canadian Trotskyist group called the International Socialists (or IS). Bearing a classic Spart headline (“Protest I.S. Thug Attack on Trotskyists! I.S. Draws Blood Line in ‘Death of Communism’ Frenzy”) the pamphlet is all but unintelligible, though the language, if not always coherent, is vigorous. It describes the fight (which broke out at an International Socialist forum the Sparts were picketing) as a lurid melodrama: “Our comrades . . . were surrounded by dozens of I.S. supporters . . . who quickly went berserk. Six I.S.ers slammed a leading comrade to the floor while McNally seized him around the throat and throttled him.” (There is a certain plausibility to this tale: more than a few among the left have felt the occasional impulse to throttle a Spart.)

It goes on. “What lies behind this frenzied assault? For years the I.S. and its international co-thinkers, who now worm around the bourgeois feminist abortion-rights milieu, have acted as loyal ‘left’ lieutenants in the imperialists’ campaign to smash each and every gain of the October Revolution and prop up rotting capitalism in the West. In Afghanistan they lusted for the blood of Soviet soldiers, supporting the CIA backed 7th-century Muslim fanatics who skin schoolteachers alive for teaching little girls to read. . . . In its vicious anti-communist ‘red hunt’ the I.S. . . . aspires to play the same role as the German social-democratic bloodhounds who after World War I worked to drown the German workers revolution in blood, murdering Communist leaders Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht and hundreds of other working-class fighters.”

What’s remarkable here is not only the peculiarity of the logic, and the almost hallucinatory grandeur of the imagery, but the idea that any group could expect outsiders reading a pamphlet such as this to have the faintest idea of what they were talking about. Rhetoric, after all, is supposed to be the art of persuasion.

In many ways the most interesting pages of WV are those given over to the Spartacist youth, who approach the league’s crusades with an almost endearing innocence: what they lack in sense they make up for in enthusiasm. Last year the young Sparts became involved in a battle of sorts with the “bourgeois feminist” groups WAC and WHAM in New York. As far as I can make out from media reports, the women’s groups, fed up with Spartacist disruptions of their meetings, attempted to ban the selling of Workers Vanguard in their meeting hall. (The battle took on proportions heroic enough to be mentioned in passing in the Village Voice as well as the Workers Vanguard, but I still can’t piece together a reliable account of the incident.) The Young Spartacists used the opportunity to make a dramatic political “intervention,” denouncing the trendy WACers as “piglets” in “bicycle shorts” and “Gaultier bras.” The Sparts ended with a statement of revolutionary intent : “WAC? WHAM? Thank you Ma’am . . . we’ll stick with Lenin and Trotsky!”

If the Sparts have little respect for other groups on the left, they have just as little regard for their political struggles. For the Sparts, struggles for reform are pointless unless they can be used to spread the Spartacist line and to recruit new members. In the mid-80s, for example, the Sparts found nothing incongruous in attending abortion-rights rallies with signs supporting the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. You see, old Leon Trotsky, despite his critique of Stalin, argued for a limited defense of the USSR on the grounds that, however deformed, it was at least better than capitalism. A photo in one recent issue of WV shows a Spartacist League banner supporting abortion alongside another Spart banner reading (and I’m not making this up): “No to the Veil! Defend Afghan Women! Support Jalalabad Victims of CIA Cutthroats!” This may be part of an artful plan to confuse the hell out of Operation Rescue, but somehow I doubt it.

To the casual observer much of this behavior may seem bizarre, but there is a certain logic to the Spartacist game plan. The world of American Trotskyism has always had a certain hothouse atmosphere to it. Throughout the years, Trotskyists, perpetually small in number, have put a premium on keeping their program correct, on protecting the “clarity” of their line from any deviations (bourgeois deviations, of course) that might come from prolonged exposure to the complexities of the world.

There is something admirable about all this: Trotskyists have stood by their principles even in the worst of times–denouncing the crimes of Stalin in the 1930s, when the left was dominated, in this country and around the world, by apologists for the brutal dictator; looking upon the third-world revolutions of the 1960s with a properly skeptical eye, when most on the left were lost in uncritical celebration. It’s hard not to feel a certain sympathy for the Trots. (Some of my best friends, as they say . . . ) But at the same time the Trotskyists have let their concerns with proper theoretical clarity blind them to the ways in which their labyrinthine ideological constructs have served to isolate them from those they are presumably trying to reach.

The American writer and critic Dwight Macdonald, who traveled through the Trotskyist movement in the late 1930s and 1940s, found his radical comrades caught in a kind of “metapolitics,” transforming every small difference of opinion or personality into a bitter and overdramatized ideological battle. “We behaved,” he recalled, “as if our small sects were making History, as if great issues hinged on what we did, or rather what we said and wrote.” There was always, Macdonald said, a dramatic “contrast between the scope of our thought and the modesty of our actions.” He and his comrades could argue for days, splitting the tiniest of radical hairs, but were utterly incapable of relating their carefully worked-out positions to anyone but each other. It was all, he later concluded, “rather like engraving the Lord’s Prayer on the head of a pin.”

There’s something oddly comforting in a sectarian existence, regardless of politics. Those who can grasp the basic formulas of the group gain a kind of ideological skeleton key to the world, picking up a broad and systematic (if shallow) knowledge of history and politics. It takes a certain intelligence–and a great deal of knowledge–to split hairs the way the Sparts do; like all other fundamentalists who base their beliefs on a literal reading of a sacred text, the Sparts know their literature forward and back. (Their interpretations may be a little wooden, but good Sparts can quote Lenin and Trotsky at the drop of a hat.) It also takes a certain dedication to continue putting forth views that are met year after year with almost nothing but derision and sometimes laughter. Like it or not, the Sparts are good at what they do. Then again, so are the Jehovah’s Witnesses.

…………………

Workers Vanguard – May 2023